Updated: October 2022

Listening to the baby’s heart rate during labour is considered to be an important aspect of routine midwifery care. There are two methods of listening—intermittent auscultation (IA) and continuous electronic monitoring (CEFM) via a cardiotocograph machine (CTG).

This post is not going to discuss the technical ‘how to’ or ‘what to look for’ when listening to baby. Instead, this is more of a reflection on the evidence and practice of listening and how it might be done in a more woman-centred way.

Intermittent Auscultation (IA)

In the 1800s physicians and midwives began using fetal stethoscopes to listen to babies’ hearts through women’s abdomens. Initially, this was only carried to assess if the baby was alive during complicated births. It was not routine. You can read more about the history of auscultating the fetal heart rate in an article by Maude, Lawson and Foureur (2010).

The Pinard (pictured) was designed by Adolphe Pinard a French Obstetrician and founder member of the French Eugenics Society. The electronic hand-held Doppler is also named after the man who invented it – Christian Doppler.

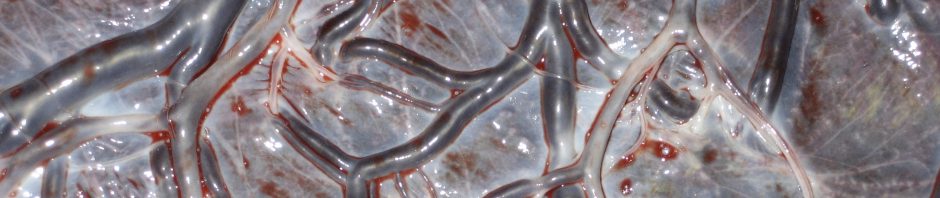

With a Pinard you can hear the baby’s heart sounds directly. That’s why it is important for midwives to be skilled in its use. A Pinard should be used before starting any electronic monitoring to ensure the heart rate is being accurately recorded. The Doppler uses short pulses of ultrasound waves to detect movement and turns those movements into sound. It can create a ‘fetal heart rate’ sound out placental or maternal blood vessels. At CTG can do the same.

The evidence

IA is recommended in clinical guidelines for all ‘low risk’ women during labour. The recommended frequency of IA is usually every 15-30 minutes during the ‘first stage’ of labour and after every contraction (or more often if contractions are longer than 5 mins apart) during the ‘second stage’. Of course, this raises questions about the concept of ‘stages’ of labour, but that’s a whole other blog post. However, there is NO research to date examining whether the practice of fetal heart rate auscultation improves outcomes, or the optimal frequency of auscultation. If you follow the citations in guidelines, they cite each other and occasionally you find a study by Kaunitz et al. 1984. This study did not specifically assess IA. In the researcher’s words: “We investigated perinatal and maternal deaths occurring among women who were members of a religious group in Indiana; these women received no prenatal care and gave birth at home without trained attendants.” There was a significantly higher rate of perinatal and maternal death in the religious group, leading the researchers to conclude that: “Women who avoid obstetric care have a greatly increased risk of perinatal and maternal death.” However, there were more pre-term and growth restricted babies in the religious group. And, this study did not indicate that fetal heart rate monitoring was the factor causing the different outcomes.

I have been unable to find research specifically exploring women’s experiences of IA (surprise, surprise). If you find some, let me know.

There may be theoretical and experiential evidence to support the practice of IA, and to be honest, I think it is here to stay. There will never be a good quality RCT to assess the effectiveness of IA because it would be unethical to allocate a group of women to labour without IA. This intervention is a firmly embedded cultural norm that women usually expect from their midwives during labour. However, we need to consider how this intervention is carried out.

Some concerns about prescriptive IA

While hearing a ‘normal’ fetal heart rate can be reassuring for both midwife and mother, there are a number of issues associated with the IA:

- The frequency of IA has been plucked out of the air and increases without evidence (the excessive IA during pushing is relatively new).

- IA involves doing something to the birthing woman – anything you do may interfere with the physiology of birth (ie. stimulate the neocortex and disrupt instinct).

- The woman may have to move from an instinctively perfect position so that you can ‘get in’ to listen.

- IA can create anxiety and concern if the heart rate is difficult to find or not ‘normal’. In the pushing phase of labour, 75% of babies will have an ‘abnormal’ heart rate due to normal physiological processes such as head/neck compression (Sheiner et al. 2001). Abnormal patterns in the ‘second stage’ are only significant if there were abnormal patterns in the ‘first stage‘ of labour (Sheiner et al. 2001; Loghis et al. 1997; Wu, Chen & Wang 1996).

Suggestions for IA

Before labour discuss IA with the woman:

- Reinforce that she is the expert in her baby’s well-being. Encourage her to connect with her baby and trust her instincts regarding their health in pregnancy, labour and beyond.

- Find out how often would she like you to listen to her baby, and if she would prefer you to use a Doppler or a Pinard? Explain that she can change her mind at any time during labour about when and how you listen to her baby.

- Explain that while she is pushing her baby out there will be some changes to the heart rate pattern and that this is normal.

- Explain how you plan to listen to her baby (see below) and check that she is happy with this approach.

During labour:

- Fit the timing of IA around the woman’s preferences and what is going on rather than set time intervals.

- Avoid stimulating her neocortex by asking, ‘can I listen in?’ Instead, gently move towards her with the Doppler/Pinard. Have a prior agreement that she can move away or push your hand away if she doesn’t want you to listen.

- If the heart rate has been normal throughout the labour, and there are no risk factors (eg. coached pushing) – there is no need to increase IA during the pushing phase.

- When the baby’s head is crowning, it can be incredibly difficult and uncomfortable to locate the fetal heart sounds because of the position of the baby in the pelvis. Instead, observe the colour of the baby’s scalp to assess oxygenation—a nice pink scalp = a well-oxygenated baby.

I am aware that my suggestions may be difficult for midwives caring for women they don’t know in a hospital setting. As usual, I am being idealistic rather than prescriptive.

Continuous Electronic Fetal Monitoring (CEFM)

Clinical guidelines recommend CEFM for ‘high risk’ women and warn against it for ‘low risk’ women. Despite recommendations, CEFM is a cultural norm in many birth settings for all women. CEFM is yet another intervention that was introduced without evidence to support its effectiveness at improving outcomes.

Most clinicians working in hospital settings will have regular training in interpreting cardiotocograph (CTG) traces. In my time as a midwife, I have completed many hours of CTG training and taught CTG assessment to midwives and students. I actually enjoyed the systematic nature of working through a trace. So, I find it disappointing to acknowledge that the apparently ‘concrete’ interpretations of the wiggly lines on the paper are not so concrete.

The Evidence

A Cochrane Review (Alfirevic et al. 2017) compared CTG with IA during labour for low-risk, medium-risk and high-risk women. The studies included ranged from the 1970s to 2016 and had categorised risk in contradictory ways. For example, some categorised induction as ‘low risk’. The review concluded: “CTG during labour is associated with reduced rates of neonatal seizures, but no clear differences in cerebral palsy, infant mortality or other standard measures of neonatal wellbeing. However, continuous CTG was associated with an increase in caesarean sections and instrumental vaginal births. The challenge is how best to convey these results to women to enable them to make an informed decision without compromising the normality of labour.” So, the only improved outcome for women with CEFM was a reduction in the overall neonatal seizure rate from 30 in 10,000 (IA) to 15 in 10,000 (CTG). Interesting, this difference was not significant for ‘high risk’ women and was most significant for ‘low risk’ women. Neonatal seizures are a short-term outcome, and there were no significant long-term outcomes eg. cerebral palsy.

A more recent systematic review and network meta-analysis (Bassel et. al 2021) looked at IA vs CTGs and the associated new technologies (fetal blood sampling, lactate assessment, etc.). It did not find a difference in newborn outcomes (acidemia, SCN admissions, low Apgar scores or perinatal death). The authors concluded: “Compared with other types of fetal surveillance, intermittent auscultation seems to reduce emergency cesarean deliveries in labour without increasing adverse neonatal and maternal out comes. New fetal surveillance methods did not improve neonatal outcomes or reduce unnecessary maternal interventions.”

A large retrospective study (Heelan-Fancher et al. 2019) explored the impact of CEFM on women with low-risk pregnancies in two States in the US. CEFM increased the c-section rate and the instrumental birth rate in both States. In one State it reduced the risk of neonatal mortality for early term babies (37-38+6 weeks). The authors conclude: “The study results do not support universal use of CEFM in pregnancies that are low-risk and at term.”

Small et al. (2020) conducted a literature review or studies looking at CEFM for ‘women at risk‘. Of the 26 studies included, 21 were at ‘critical or serious risk of bias’, and therefore excluded from the review. In the 5 studies reviewed, there was no difference in stillbirth or neonatal death. They found that CEFM during pre-term labour was associated with a higher incidence of cerebral palsy. The authors state that “Research evidence failed to demonstrate perinatal benefits from intrapartum cardiotocograph monitoring for women at risk for poor perinatal outcome.”

So, there you go… confusing and conflicting research findings regarding CFM and newborn outcomes. Yet, very clear findings regarding the increase of c-section and instrumental birth for women with CFM.

Research looking at women’s experience of CFM is limited. A systematic review (Crawford et al. 2017) of 5 studies found that CFM “was reported to have high levels of participant satisfaction and was preferred by women to intermittent cardiotocography.” Which is not surprising if women think it improves outcomes for their baby (and were they told of the increased risk of surgical birth?). The authors conclude: “This review suggests that continuous fetal monitoring is accepted by women. However, it has also highlighted both the paucity and heterogeneity of current studies and suggests that further research should be conducted into women’s experiences of continuous fetal monitoring before such devices can be used clinically.”

An ethnographic (qualitative) study explored clinicians’ experiences of centralised CEFM. The findings are published in two journal articles (Small et al. 2021; Small et al. 2022). I’m sure there will be no surprises in the findings for anyone working in settings with centralised CEFM:

“The introduction of the central monitoring system was associated with clinical decision making without complete clinical information. Midwives’ work was disrupted. Higher levels of anxiety were described for midwives and birthing women. Midwives reported higher rates of intervention in response to the visibility of the cardiotocograph at the central monitoring station. Midwives described a shift in focus away from the birthing woman towards documenting in the central monitoring system.” (Small et al. 2022)

“Midwives described a disruptive social event they named being K2ed. Clinicians responded to perceived cardiotocograph abnormalities by entering the birth room despite the midwife not having requested assistance. Being K2ed disrupted midwives’ clinical work and generated anxiety. Clinical communication was undermined, and midwives altered their clinical practice. Midwives performed additional documentation work to attempt to avoid being K2ed.” (Small et al. 2021)

The researchers raise concerns about centralised CEFM and conclude: “This is the first report of an unintended consequence relating to central fetal monitoring, demonstrating how central fetal monitoring technology potentially undermines safety by impacting on clinical and relational processes and outcomes in maternity care.” (Small et al. 2021)

Like IA, CEFM, particularly for women with ‘high risk’ pregnancies, is here to stay. There is too much invested financially and culturally to withdraw this questionable and widespread intervention. In addition, it is important to assess the impact of any intervention on mother and baby. Personally, I would be very concerned about carrying out an induction of labour without CEFM of the baby. The risks are too high and being able to see the baby’s response provides a sense of control and safety (a rite of protection) regardless of evidence. However, it could be argued that putting a CTG on a ‘low risk’ woman having a spontaneous labour creates risk and danger.

Suggestions for CEFM

- Discuss the evidence with women and provide adequate information about the benefits and risks to gain consent (or for her to decline).

- Discuss the process ie. what it involves (eg. that other staff may assess the trace), and options (eg. does she want the monitor turned away from her? the volume turned down? an explanation of the trace or just an overview ie. ‘it’s good’), what will happen when a variation or abnormality is identified.

- Fit the monitor around the woman. Even CTG monitors with straps can be used while the woman is mobile (obviously dependent on epidural).

- Make sure you get a decent trace. There is no point in having a CTG on if it is not effectively recording a trace.

It would be great if you could leave your tips for woman-centred CEFM in the comments.

Further reading/resources

- Reclaiming Childbirth as a Rite of Passage (Reed 2021)

- Intelligent Structured Intermittent Auscultation (ISIA): evaluation of a decision-making framework for fetal heart monitoring of low-risk women (Maude et al. 2014)

- Putting intelligent structured intermittent auscultation (ISIA) into practice (Maude et al. 2016)

- Intermittent auscultation (IA) of fetal heart rate in labour for fetal well-being (Maude et al. 2017)

Comments transferred from previous blog:

Holly Meyer

Thank you for posting this Rachel. I have often thought about this, as home vs hospital is so different. In the 2 homebirths of my own babes I didn’t want IA. My rationale for this was that I was concerned if I heard an abnormal heart rate/tone that it could send me into panic, pulling me out of my ‘birth space’ or ‘labour land’ and focussing on something that may or may not be of concern. Thus beginning a cascade of fear.

Your suggestions for ways to offer IA to mothers enabling them to make informed choices backup my own feelings on the subject and will be very helpful in my practice.

LOVING this blog, and I look forward to more entries!

Tuesday, July 27, 2010 – 07:43 AM

Rachel

Thanks Holly!

I find IA difficult. On the one hand we are saying to the mother ‘trust your body and your instincts’ then the next moment we are checking that her body is working and the baby is safe.

Most of the women I care for choose ‘occasional’ IA that fits around them. Some want more regular IA – especially those who have been fed fear during pregnancy (eg. VBAC).

As a midwife I do like to hear a normal FH. But then as you said – if there is a transient change eg. tachy due to dehydration/heat I stress (on the inside only I hope) until it returns to normal. I am also aware that prescriptive IA is the standard legally regardless of evidence.

Anyway, I’m pleased you like the blog. I plan to post at least once a week and keep focussed on midwifery practice rather than the depressing politics.

Rx

Tuesday, July 27, 2010 – 08:46 AM

Anna Robins

Loved your suggestions, which really hand the power back to the woman and recognise her right to making an informed decision regarding her labour. Also, lovely pinard !!

Wednesday, July 28, 2010 – 10:58 PM

This is a lovely post! I have shared it with my facebook world! Information coming to me this year is letting me look at those OP babies as another variation of normal. Reframing this in the context of the birth is helpful to all! thanks for writing this so well!

Sharon

Great post! I shared it on the CNY Doula Connection facebook page.

Thanks!

I’ve just found your blog and love it. Thank you.

My partner and I did a hypnobirthing course before the birth of my daughter last year but chose to deliver in hospital as it was our first baby. Our birth plan (aka ‘leave us alone’) was, on the whole, followed well by hospital staff and the membranes were intact for all except the last 30 minutes of labour. At this point I was in the birthing pool and felt them burst with a contraction. The midwife listened to the baby’s heartbeat immediately afterwards and because it ‘dropped’, told me I had to get out of the pool. I gave birth to Brianna on my side on a hospital bed.

Although I was happy with the ‘natural’ birth I had, I can’t help wondering if I could have stayed in the pool. My thoughts/instincts are that anyone’s heart rate would drop if the environment they’d been in for 9 months suddenly blew up around them! Do you think there’s a chance the heart rate would have recovered? It wasn’t really given a chance to. The reason I ask is that I’m due to give birth again at Christmas and am planning a home birth with birthing pool. The videos you’ve provided links to have been so inspirational, I would LOVE to give birth in water. I know I will have more choice this time but would like to feel confident that the hospital midwives were being over-cautious when they hauled me out of that pool!

Even if you don’t get the chance to respond, I’d like to say how much confidence reading your blog and watching the videos have given me to birth at home. I haven’t yet decided whether to hire an independent midwife but this is an option we are considering.

Warmest regards,

Andie B (UK)

Hi Andie

Your thoughts and instincts are probably right. Often when the waters break and the baby descends quickly into the pelvis you will hear a deceleration – this is a normal response and will usually recover once the baby adjusts. Let me know how your waterbirth goes.

Rx

I am a Brit who has had four sons between 1986 and 1990 the last as a home birth and I am absolutely convinced that audible foetal heart monitoring in hospital is causing increased anxiety and increased interventions in what should be a quiet, labouring-mother led process. The foetal heart rate is approx 140 bpm compared with 70-80 bpm adult resting rate – the baby’s heart therefore sounds like its racing and in a panic which makes everyone hyperviigilent and anxious.This means that any and every slight fluctuation is over analysed and leads to defensive interventions which are unnecessary and intrusive. I suggested to our National Childbirth Trust that they sponsor some research into this so I am very interested in Robyn’s research- Keep up the good work!

I know of a Mom who had a boy #5 pregnancy that had his cord completely knotted tightly….the doctors could not believe it…he is a healthy young man today !

First off I want to say great blog! I had a quick question which

I’d like to ask if you don’t mind. I was interested to know how you center yourself and clear your mind before

writing. I have had a difficult time clearing my mind in getting my ideas out there.

I do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15

minutes are usually wasted simply just trying to figure out how

to begin. Any recommendations or tips? Many thanks!

If the frequency of measuring the fatal heart rate is hospital policy, can a women refuse to be monitored at that frequency? or at all? Or is it compulsory in a hospital setting?

Not sure where you are from Tina. However, no one can touch you (i.e. to listen to your baby) without your consent. You have the right to decline health care including monitoring.

I’m in Melbourne Australia. That’s good to know, thanks

I visited multiple sites except the audio quality for audio songs current at this website is actually wonderful.

I totally and utterly agree with this. I am currently planning my own birth no3 and this will be on my request list. In fact if I can find a technology that allows a “contactless” IA to take place then I will use it. I don’t want voices and hands touching me without need and just to fit into a neat protocol.

I attempted a homebirth (a vbac), which was finally a vaginal birth that started at home and ended in a hospital. My baby had an Apgar of 9, so he was perfect. I labored for 2 days, finally the water broke and I felt the need to push, so push I did whenever I felt like it and in the position I felt comfortable. My midwives listened to the baby’s heart rate in between contractions, so we found out that my baby’s heart rate was dropping and not recovering in between, so we decided to transfer to the hospital. Is this considered standard practice? I had been pushing for an hour, I was tired, but I was very determined to give birth at home. When they told me the baby could be in danger, of course the decision seem obvious. But is this correct? If the heart rate drops IN BETWEEN contractions, is it a sign that something might be going wrong?

THANK YOU!

Yes – when the baby’s head is in the vagina and a contraction happens his head gets compressed. This stimulates the vagal nerve and makes the heart rate drop. Once the contraction goes the compression of the head and vagal nerve releases and the heart rate (should) rise back to normal. If the drop in heart rate happens between contractions it can indicate that the placenta is not sending enough oxygen to the baby and the baby is becoming hypoxic. It would be standard practice to transfer from a homebirth in this situation. Chances are the baby will compensate and be born OK if it does not go on for too long… but it could also result in the baby needing assistance to come out quicker and/or resus after birth. I hope that makes sense 🙂

Crystal clear!! Thank you so much for your explanation, I feel relieved that it was the right move to make.

I love your blog, I’ve learnt a lot reading you. Thanks for sharing so much wisdom.

It’s impossible to know what was happening though right? I keep wondering WHY the placenta wasn’t sending enough oxygen, given that there was no directed pushing and we let my body be the guide of what I needed, changing positions and so. It was a super healthy pregnancy, I was fully dilated, the baby was in optimal position.

Sometimes these things happen and we never know why… despite optimal conditions. I guess that is why globally and historically women rarely birth alone and usually choose to have other women be there to monitor and assist if needed. If you look at nature ie. animal birth – not all mothers and babies make it. Humans have attempted to minimise this loss with ‘interventions’ such as listening to the fetal heart and management of complications. And in many cases they succeed 🙂

Reading you is always such a pleasure. Thank you. <3

My son’s hear rate fell to 8 beats per minute at one stage during my labour and if his heart rate had not been monitored, my mid-wives would not have known to change my position urgently, (which resulted in his heart rate recovering and ultimately saved his life). He was delivered by C-section 14 hours later with a birth Aphgar of 4 but is now a healthy 10 year old. A very lucky boy but testament to the fact that science can save lives which must surely be considered above bonding, birth plans and maternal anxiety levels.

I have justfound that my AFL IS 4.2 WITH (single pocker) does this pose any risk to mybaby what i should ?

Your care provider who arranged this assessment needs to explain the findings to you. They will have all of the relevant information.

I love this blog. This article is EXACTLY what i am doing my dissertation on and have found little research on the topic. Most research focuses on continuous monitoring vs IA, rather than IA itself. Ruth Martis is the only other author that has written about this too. Have you any others links you could suggest?

There is very little research on IA. It all focuses on CTG machines. Not surprising considering the birth culture.

Robyn Maude has published more about IA since I wrote this post. I’ve added some links to her work at the bottom of the post

Good luck with your dissertation! 🙂

Can we talk about the problem with monitoring, especially CTG, in posterior births? My VBAC baby was posterior, and the staff had difficulty finding a trace because of his position – so immediately and very strongly tried to coerce me to have an emergency c (it didn’t work). Eventually they convinced me to have a scalp clip (which I didn’t want) instead, which showed a perfectly normal heart rate and happy baby. I went on to push him out, but what of the women who didn’t know better? What can we do in this situation? Does CEFM need to improve to better cater for babies in a posterior position? Or does hospital policy need to be less reliant of it and better understand posterior birth?

I have never heard of this scenario. CEFM usually picks up the fetal heart rate without any problem with a posterior baby. Same with a doppler. ‘Loss of contact’ is common but I’ve never heard of a posterior position being blamed…

I’ve never heard of a posterior position being blamed for inability to get a good CTG trace! The electronic devices (doppler and CTG) can easily pick up a heart rate through the baby’s chest.

Hi Rachel. I’m wondering if you could shed some light re the actual methods used for IA. The (public) hospital I am currently working at state we *must* listen to the FHR prior to, during and for at least 60 seconds after a contraction (which differs from national guidelines). I am so upset at this, because I know this would be leading to the detection of non-pathological decels and therefore the cascade of intervention. and I am also concerned about the fact we have a whole cohort of midwives practicing and performing AI incorrectly..

The methods are not evidence based… they are cultural norms. And they keep changing to be longer listens with shorter duration between ie. attempting to mimic continuous EFM. I guess it is a case of asking women what they want – there is no ‘must’… only a recommendation. It is up to the woman if she wants that level of monitoring.

Amazing post Rachel!

I love your recommendations.

Would you have any more specifically for educating women antenatally or working as a midwife in the system how we can inform women?

I know in my hospital a high risk women declining CTG would be a massive battle. Also personally I’m not sure where I would sit comfort level on a high risk with no CTG although I have full belief that it increases CS rate!

That would be a long answer! In short… we need to remember that as midwives we are ‘with woman’… it is about being honest with women about the recommendations vs the evidence and that ultimately they decide… it is their comfort level… and of course that is all caught up with nurturing self-trust – a concept I write about in my book Reclaiming Childbirth.

Discussion with our private midwife show they respects my decision to not have Doppler through pregnancy but says she would feel uncomfortable not using it during labour as “how will she know if something is wrong with the baby”. I expressed that I have concerns that the use of the Doppler during my labour will be distracting and asked would it not just be used if things seemed amiss, the answer was some what unclear to me and tinged with apprehension. Thank you for writing this article, I hope it will assist me in advocating for what I want albeit I am already tired from all the necessary advocating.