Updated: January 2023

This post is about routine vaginal examinations (VEs) during physiological birth ie. an uncomplicated birth without any medical intervention. The VE is a useful assessment in some circumstances, but it’s routine use in an attempt to determine labour progress is questionable. As birth knowledge evolves, and research challenges the current cervical-centric approach to labour progress, there is an opportunity to shift practice. I’m hoping this post will inspire readers to reconsider their beliefs and practices regarding cervixes and VEs.

History: the rise of the cervix

To understand why we go so fixated on what one small area of the body is doing during birth, we need to look at history. The following is based on content from my book Reclaiming Childbirth, where I explore history in more depth. Here is a quick overview:

98 AD to 1900s

Vaginal examinations were only carried out during complicated births, for example, to assess if the baby was mal-positioned. They were not used to determine progress of labour. Early midwifery textbooks warned against routine vaginal examinations. For example, in the 1700s French midwife, Madame du Coudray wrote: Too much vaginal meddling is bad too: the best thing is to wait patiently, alert to all cues.

1900 to 1970s

Social and cultural changes resulted in childbirth moving from the domestic domain of the home into the medical domain. Influenced by the development of industry and technology, the body was conceptualised as a machine, with distinct parts that could be studied and understood separately. The birthing woman was ‘broken’ into physical parts – uterus, cervix, baby – and a systematic, linear understanding of labour progress developed. This is still evident in modern textbooks. The woman has disappeared in favour of diagrams depicting her ‘parts’ (and the fetal skull) alongside precise measurements. This simplified and incorrect understanding has underpinned education about birth and practice during birth.

In the 1950s, an American obstetrician named Emanuel Friedman plotted onto a graph the cervical dilatation of 500 women having their first baby in a hospital. The study population included women who were sedated and had medication (Pitocin) to induce or speed up their labour, and 55% had forceps. The study found that most women had birthed within 12 hours and when averaged out cervixes dilated 1cm per hour. However, individual women’s cervixes did not do this in a linear way. Instead, some women dilated faster, then slower or vice versa. However, the averaged-out, neat and linear graph became established.

In the 1970s, based on this reductionist and linear approach, the partogram became established within medicalised maternity systems. In his 1978 textbook Labour: clinical evaluation and management Friedman describes labour assessment: The phase of maximum slope is a good measure of the overall efficiency of the “machine” with which we are dealing. The aim of the partogram was/is to measure and control labour progress by plotting cervical dilatation onto a graph, along with descent of the baby’s head. If the cervix does not open along the prescribed timeframe (1cm per hour or 0.5cm per hour depending on the hospital), labour will be augmented ie. speeded up with an ARM or synthetic oxytocin.

Now: new understandings and contradictions

Research

In recent years, new knowledge about birth physiology and research has challenged the cervical-centric approach to labour progress assessment. A previous article/post discusses the research regarding labour patterns and partograms. In summary, the research shows that women’s labour patterns do not fit the timeframes prescribed by partograms. A Cochrane Review (2018) on the use of partograms in normal labour concluded that: On the basis of the findings of this review, we cannot be certain of the effects of routine use of the partograph as part of standard labour management and care, or which design, if any, are most effective. Further trial evidence is required to establish the efficacy of partograph use per se and its optimum design. The findings of a large study by Oladapo et al (2018) also challenged the accuracy of partograms concluding that: Averaged labour curves may not truly reflect the variability associated with labour progression, and their use for decision-making in labour management should be de-emphasized.

Partograms and VEs go hand in hand – filling out a partogram requires regular vaginal examinations to ‘plot’ along the graph. However, there is no evidence that routine VEs in labour improve outcomes for mothers or babies. A Cochrane Review (2022) concluded that: Based on these findings, we cannot be certain which method is most effective or acceptable for assessing labour progress. Another recent study (Ferrazzi et al. 2015) found that cervical dilatation during spontaneous natural labour is non-linear and unpredictable.

Without adequate evidence for the use of the partogram, or routine VEs there is increasing debate in academic circles about the way forward. Unfortunately we are so cervical-centric that the proposed solutions still involve cervical measurements, and therefore VEs. For example, Zhang et al. 2015) in their article state: …any labor curve is illustrative and may not be instructive in managing labor because of variations in individual labor pattern and large errors in measuring cervical dilation. With the tools commonly available, it may be more productive to establish a new partogram that takes the physiology of labor and contemporary obstetric population into account. At the ICM Conference in Prague (2014) and at the University of California it was proposed that the partogram (ie. the clock) should be started at ‘6cm dilated’ rather than the current ‘3-4cm’ to avoid unnecessary intervention.

There is also reluctance to change hospital policies, underpinned by a need to maintain cultural norms. The Cochrane review on the use of partograms on the one hand states that they cannot be recommended for use during ‘standard labour care’, and on the other hand states: Given the fact that the partogram is currently in widespread use and generally accepted, it appears reasonable, until stronger evidence is available, that partogram use should be locally determined. Once again, an intervention implemented without evidence requires ‘strong’ evidence before it is removed. The reality is that we are unlikely to get what is considered ‘strong evidence’ (ie. randomised controlled trials) due to research ethics and the culture of maternity systems. Guidelines for care in labour continue to advocate ‘4 hourly VEs’ and reference each other rather than any actual research to support this (NICE, Queensland Health).

The cervical-centric discourse is so embedded that it is evident everywhere. Despite telling women to ‘trust themselves’ and ‘listen to their body’, midwives define women’s labours in centimetres She’s not in labour, she’s only 2cm dilated. We do this despite having many experiences of cervixes misleading us ie. being only 2cm and suddenly a baby appears, or being 9cm and no baby for hours. Women’s birth stories are often peppered with cervical measurements I was 8cm by the time I got to the hospital. Even women choosing birth outside of the mainstream maternity system are not immune to the cervical-centric discourse. Regardless of previous knowledge and beliefs, once in the altered state of labour women often revert to cultural norms. Women want to know their labour is progressing and there is a deep subconscious belief that the cervix can provide the answer. Most of the VEs I have carried out in recent years have been at the insistence of labouring women – women who know that their cervix is not a good indicator of ‘where they are at’ but still need that number. One woman even said I know it doesn’t mean anything but I want you to do it. Of course, her cervix was still fat and obvious (I didn’t estimate dilatation)… her baby was born within an hour.

Physiology

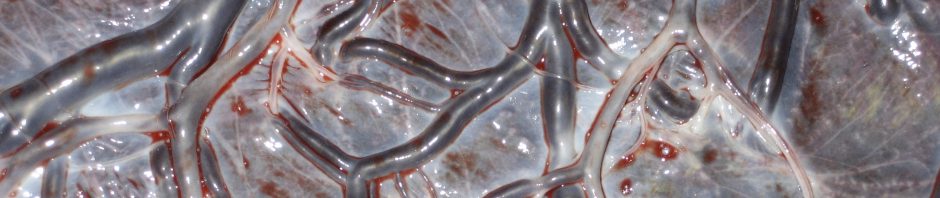

The idea that the cervix can tell us about progress in labour is underpinned by an incorrect understanding of birth physiology. Childbirth physiology is complex (I have an entire course just on this topic). The uterus transforms during labour rather than the cervix simply opening.

Vaginal examinations: not just a benign procedure

In order to gain consent for a VE, women need information about the lack of evidence supporting VEs, and about the potential consequences of VEs. I’ve started a list below and welcome any additions you can think of:

- VEs are invasive and often painful: There is limited research into women’s experiences of VEs (surprise, surprise). Most women report being ‘satisfied’ with their VE experience, some find it painful, for a few VE is associated with PTSD (Dahlen et al. 2013). I’d be interested in your comments about experiences of VEs.

- The findings can be misleading: What the cervix is doing at the moment of a VE does not indicate what the cervix is going to do in the future. Therefore, the findings cannot effectively inform decisions about pain medication or other interventions (although this is often the rationale given for performing them).

- The measurements are subjective and inconsistent between practitioners: The accuracy between practitioners is less than 50% (Buchmann & Libhaber 2008).

- A VE disregards the woman’s knowledge and reinforces the external expert. Often the findings do not match the woman’s experience and the result can be disempowering, for example in early labour.

- A VE can result in accident rupturing of the membranes: It is not uncommon to accidentally break the amniotic sac whilst carrying out a VE – this alters the birth process and increases risk for the baby.

- VEs can increase the chance of developing an infection (Dahlen et al. 2013).

Other ways of knowing

The truth is that women’s bodies are complex, unique and immeasurable. Birth is a multidimensional experience that cannot be accurately defined by anyone outside of the experience. We – those of us who give birth and/or attend birth – know this. Midwives already assess labour based on other (less invasive) ways of knowing. In my PhD findings midwives’ birth stories were filled with descriptions of mothers’ behaviour. One participant said: It’s like a performance… at this stage of this performance what is it saying? And… it’s not what she’s saying, it’s what she’s not saying. And it’s what she’s displaying, the way she’s moving, what her body is doing in a physiological sense. Other studies have also described this approach to labour assessment. Dixon et al. (2014) mapped their research about the emotional journey of labour with findings from previous studies, and integrated this with physiology. Duff (2005) studied women’s behaviour during labour and created an alternative ‘partogram’ based on her findings. There are also physical changes that occur to women’s bodies during labour that can be seen and indicate labour progress (eg. the shift of the Rhombus of Michaelis and the purple line). It is not within the scope of this post to discuss these behaviours in depth (perhaps a separate post?). I am just trying to point out that the cervix is not the only indicator of labour progress. Yes, women’s behaviours are individual and may not fit any expected patterns, therefore relying on these methods may be misleading sometimes. But VE’s are also inaccurate and misleading (see above)!

Suggestions for midwives

- Be mindful of language and how we communicate about labour to each other and women. Stop talking about centimetres and start talking about behaviours and other signs of progress.

- During pregnancy: provide women with honest information about VEs, their limitations and the potential consequences; and the alternatives. This should also include information about policies in their chosen birth setting, and their right to decline policy recommendations.

- Care in labour is influenced by the setting. For example, a hospital may have a policy of ‘4 hourly VE’s’ – and as an employee you are obliged to follow policy. However, your obligation is to offer a VE, not to carry it out. To do a VE without consent is assault and battery and a breach of professional standards. If you provide the woman with adequate information (see above), and make it clear that this is an ‘offer’ based on policy (not your own needs), and that from all external signs she is progressing well… some women will decline your offer. You can document her decision and carry on having fulfilled your duty to the woman and to the hospital.

- If you are in a setting where VEs are not routine (eg. homebirth) and the woman asks for a VE (which they do)… try to work out what she really wants. Does she want reassurance that all is well and she is progressing, or does she really want to know what her cervix is doing. If it is the latter, encourage her to feel her own cervix. If she insists do a VE with consent.

- When communicating the findings of a VE include other changes – “the baby has descended, rotated, flexed” and positives about the cervix “it is stretchy, soft, opening up nicely”. If she needs a number, give her one, but demonstrate that this is not important to you. Do not use the findings to dictate her behaviour, eg. pushing or not pushing.

Summary

Routine vaginal examinations during physiological birth are a symptom of a cervical-centric birth culture. There is enough evidence to support a shift away from this common intervention towards a more woman-centred approach to labour progress assessment. We need to value the ‘other ways of knowing’ that are already established, and reinforce the woman as the expert in her own birth experience.

Further resources

The Midwives’ Cauldron Podcast on assessing labour progress

If you enjoyed this post, you can find more of my work in the following resources:

Join my Mailing List to stay up to date with new content and news

Very pleased to read this article. I believe I suffer PTSD in part as a consequence of forced VEs in my first birth (and the general trauma of the experience). I find them to be excruciatingly painful. My first birth began with waters breaking and hoight VE was contraindicated after 14 hours it was still done. I screamed out and said to stop and the midwife continued saying she wanted to wait for a contraction which was unbearably painful as a consequence. I have seen the same happen on TV shows such as One Born Every Minute, so routine is the abuse of labouring women that consent and even requests to stop is happily ignored by midwives. I ended up being made to transfer to hospital and followed the usual cascade of intervention ending up with epidural – the primary relief of which was that I no longer had to feel pain of VEs. I refused them all in my second birth and yet they were repeatedly offered and requested. Six years later I have refused a variety of medical diagnostics for other conditions due to my distrust of he profession and unwillingness to let strangers anywhere near my nether regions.

When I discussed on birth forums about my plan to not have VEs in my second birth I found tha majority of women believed they are necessary. They even argued with me about it and that I would be putting my baby in danger by refusing them. Even women who had had swift unassisted births before were telling me how important VEs are!

I was very interested to note the purple line in my second birth. And you are right about the ingrained desire to monitor progress as its presence buoyed me up.

Thanks for sharing your experience. Hopefully it will make people think about how their practice is experienced. Unfortunately abuse is common in our maternity ‘care’ systems.

Sadly this exact thing happened with me just 8 months ago. I was screaming for her to stop but she didn’t, my partner had to physically remover her from me and off my bed. I’m going through counselling for pnd and ptsd as unfortunately it has also brought up things that happened to me in the past.

I am so sorry that this happened to you.

I loved reading this piece which reinforces the ideas of my Phd.

I am in year two of my study and am attempting to unveil and capture midwives’ tacit knowledge of normal labour progress, to inform a labour observation tool.

The climate is right for midwifery research to expose and evidence midwifery practice , to challenge poorly evidenced accepted norms and to really make a difference to women in labour.

I look forward to reading your findings! Good luck with your studies 🙂

Loved this, thank you. I found the advice on how to comply with hospital policy, and still avoid unnecessary VE’s very useful. I’ll be sharing this widely 🙂

Reblogged this on bellabirth: informed birth and parenting.

My VE experience. With my first my water “broke” 17 hours before my first contraction. When I told the MEDwife she insisted I couldn’t possibly know if it was really my water or urine. I was insulted and annoyed. I was 26 years old and I’m a doctor. After arguing with her and refusing immediate induction with a c/s proposed if it didn’t succeed within 5 hours (and her telling me how mad she was at me for not calling earlier so they could have started earlier and finally just lying to her she’d misheard the time by 12 hours). Then after I’d repeatedly refused VE she got me to agree to just let her swab with pH paper but no VE. Well that ended with me scooting back along the table until I was as far against the wall as possible as she stretched herself as far as she could from the stirrup end as she kept going higher to get that fluid swab.

I was angry and felt violated. At no time did she ever use u/s or fetoscope to listen to my baby and check if he was alive, the whole reason I had come in because I hadn’t felt him moving – which is normal for me.

I had 2 more painful unwanted VE in labor because I was told I couldn’t object despite having asked the director at my first visit if I could do so. No, I was not satisfied! I was violated! It’s part of why I went UC with my 3rd child!

Other useful info the MWs never asked about. My m. Grandmother had 2 long labors, my mother and m. Aunt both has their water break hours before labor started and both ran out the clock w/ c/s. My son was born 39 hours after my water broke (no labor augmentation) Apgar 9/10 and they did amniotomy w/o consent (they told me they were going to do it while I was contracting/grunting) during pushing and water from my “broken” bag gushed everywhere.

How awful that you were treated like 🙁

Thank you so much for this. I found them excruciatingly painful with my first birth. It was used as a reason not to allow me in the pool – I wasn’t 5cm dilated. I was so desperate to get in the pool (in my own home as well!) that I agreed to one. I had gone from 4cm – fully dilated in 3 hours. I had intended to labour in my pool then give birth on land. In actual fact I laboured on land and gave birth after only 45 minutes in the pool. I wrote a birth plan for my second birth and it was highlighted in red that I declined any VEs and they were not even to be offered as it would upset me. I had an intervention free birth, without midwives and got into the pool and out when I wanted. The tragedy is that the desire to know in ‘measurable’ terms is very very strong indeed. Despite me being in a lot of pain, I still felt they were the only way to know what was going on. I knew better second time. You have reassured me that I am right – just say NO!

Thank you so much for your very well written article. Early in my practice, I did a lot more VE’s, now relying much more on external indications, and checking only when no evidence of progress over time. I also remind the couple that according to scripture, their bodies belong to each other. With good hygiene and thoughtfulness, the husband can check his wife’s cervix, when they are wondering when to call. For a woman to accept a VE, there must be a certain level of trust, usually present in a healthy relationship, whether it is marital, medical, or midwife. A lack of that trust would certainly provide opportunity for discussion of any previous abuse or other issues.

The VEs in my first birth were one of the most upsetting things in what was a generally very traumatic experience. The pain took me by surprise but the worst thing was the lack of dignity, the sheer disgust I felt at having another man’s hand up my vagina (prior to that experience my husband had been the only man to ever touch me — and that had always been in a loving, consensual way). For several years after that I did not even feel comfortable using tampons, and I could not listen to birth stories involving VEs without having a strong emotional reaction. I’ve moved on since then, but it took years of conscious healing effort.

Thank you for sharing. Midwives need to ‘hear’ these stories.

I believe I also got PTSD from the intervention during my first birth. I attempted a home birth but was getting restless with how slow it was going so ended up in the hospital. They said I had a cervical lip and tried “massaging” it out with each contraction.

I’m sure I’ve blocked some stuff out, I cannot think back without my body shaking and crying uncontrollably. Even the vaginal check post birth was traumatic, on the way to the car I could hardly get there.

Thankfully my second homebirth was better, only one check, which has caused the same reaction but the rest was a good experience and I stayed at home.

🙁 – have you seen this post? Can you find some support to debrief. PTSD is not OK

I’ve told the story of my first son’s birth in centimeters. Now I won’t put quite the emphasis on those details. It was pleasant for my second boy’s birth to not concern myself about dilation at all. I’d like to share your informative article on my blog http://awonderfulbirth.blogspot.com/.

Of course you can share the information on your blog. 🙂

I felt like VEs were the only part of my care which were not up to me to decide on. My midwife gave me the option of declining everything else, including GD testing, GBS testing, antibiotics during labour, erythromycin for the baby (I declined it all). I found the VEs and S&S excruciatingly painful. I had a home birth and during transition I was begging to be transferred to the hospital for an epidural. My midwife told me that we can transfer but she has to do a VE to determine how far along I was to make sure it’s safe to transfer. Honestly the fear of the pain of the VE made me stay and give birth in my bathtub. Maybe my midwife knew that and tricked me.

Thank you so much for this post.

This is the next area of intervention that needs thorough review and practices that need to be properly evaluated.

Thanks for this thorough and insightful post. I work as a birth doula. Because our scope of practice is non-medical, we’re unable to rely on any of the “standard” labor progress tools so we rely much more on a woman’s behavior and demeanor to help assess how labor is going. Thankfully many of the midwives I have worked with, especially home birth midwives, also use these techniques–though it’s hard to imagine how OBs, many of whom have never observed an entire labor from start to finish, would be able to adopt any of these observational tools!

That’s why I kept OBs out of the post – they rarely if ever get to watch a physiological from beginning to end. This is not their knowledge and if midwives don’t start valuing it we will lose it too.

Thank you for this, it’s very thought provoking. Un-necessary ‘VE’ s are an area of interest to me as is systematic and widespread abuse if women and refusal to listen to a woman’s wishes

I read this thinking “yes! so true!” at every sentence. I hate the obsession with the cervix, and especially how we “don’t allow” women to push until it’s been “confirmed” that she has reached full dilatation. Or as it is often put, until she “is fully”. As if the cervix were the entirety of the woman!

And in contrast, when she reaches 10, she MUST push, even if she doesn’t have the urge, even if her body would take a rest and allow her a second wind. The obsession isn’t just with the cervix, it’s with the number 10.

And how many babies actually have a head diameter of 10cm? The cervix opens as wide as the individual baby’s head… 12.3cm, 11.6cm, 9.2cm … whatever is needed 🙂

Or the head accommodates the size of the pelvis: see

Cohain JS Three cases of Prolonged Second Stage of Labor 14, 17 and 24 hours. Midwifery Today 122:18-20.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1zM_aY2An1sICUIP12Gwn0b5gSP4Kzlg7HP_JpJUN6ys/edit?usp=sharing

Thanks for this empowering post Rachel.

In the final days of my wife’s pregnancy I started reading your blog and read it thoroughly to understand all the variables from a free birth or home birth perspective. The studies and examples you gave filled me with extra confidence. We were never in favour of unnecessary checking, handling and probing (I don’t think anyone is), so I was very glad to read your articles on the history of accepted birthing procedures, versus the studies indicating the help or the hindrances they create.

The birth of our daughter was incredibly empowering for all of us, and we seek to share that experience with others in the hope that they too will have as much awareness as possible going into birth. There is an unfortunate few that really want to break from cultural norms or accepted procedures out of fear of being disloyal to family, friends or the establishment.

Following the woman’s own expert intuition can require a leap of faith of sorts, but must be remembered as the primary indicator of all processes. It takes an equally conscious and present mid wife to recognise that if her job has been done well, then she will be little more than an observer of the process.

Here’s our birth story:

https://www.tenmoons.com.au/2014/12/jin-gavins-homebirth-story-011014/

Thanks again for sharing your knowledge and power

Gavin

What a beautiful birth story (from both ‘sides’) – enjoy your baby girl 🙂

I feel vindicated. As a retired midwife I reflect on practice which avoided VE’s whenever I could. There were many times when I posed the question ‘which came first…… babies or clocks?’ Nobody seemed able to give me a proper answer. I relied a lot on other signs. Having said all that, of course there were times when I was forced into a corner by weight of ‘senior’ opinion and orders.

As a mother who birthed well before becoming a midwife I look back on totally VE free labours! I serendipitously chose an OB who arrived for the birth – if you were ‘lucky’. He was often late because he would really rant at staff if he was called early!

Nobody, but nobody dared to examine ‘his’ women so no VE. He also didn’t believe in using due dates, preferring ‘early to mid-June’ type guesstimates. Therefore there wasn’t really the sense that one was overdue, so no intervention there. He relied on his antenatal findings at each visit.

And this was well before ultrasounds.

The only internal exam I ever had was at my first visit where he was getting size of uterus as the due range guide. He said something like ‘that is around a 2 month size, making you due…..(see above)’. He also did full body exam that first visit to assess body changes as indicators.

Hope that all makes sense.

Need to add. I was violated in a way though. The midwife did not trust my body. With my first, after around 4 hours of what I considered to be strong labour I felt the need to push. The conversation went along the lines of : MW ‘you mustn’t do that’ Me ‘why not?’ MW ‘because your cervix is not fully dilated’ Me ‘how do you know?’ MW ‘because you haven’t been in labour long enough’

Me ‘I’m pushing’ said AS I was doing so (you can ‘hear’ me, can’t you’). I could no more have resisted that urge than walk on the moon. Baby was born very soon after that conversation.

Thank you for this article. I wish more maternity practitioners will read and respect women during their pregnancy and childbirth. I had a VE during my labour, I didn’t want one but I consented under duress. I hated it, I felt violated and I did suffer PTSD afterwards due to that and other unwanted interventions. I find it very distressing that Drs and Midwives are either deaf or do not understand the word NO! If it’s against their belief or practice they just keep pressuring you, harassing you and bullying you.

This is so true.

There is no consent. It’s “I am doing this” as said procedure is in progress. “We have to do this.”

Thank you for this article ! It’s always interesting to deconstruct routine interventions and measurements.

Is it possible to read the bibliography please?

Thank you very much,

Solène

I have put the references into the text as links. If you click on the link you will be taken to the reference source. There is also a reference list on the ‘previous post/article’ I link to in the post which has the references re. assessing labour progress. Dahlen et al – cited and linked in the post – cover much of the content in their journal article too. The practice recommendations (unless references) are based on my experiences and/or emerge from the literature discussed. Hope that helps. If there is anything specific you are looking for – let me know 🙂

Thank you so much !

A wonderfully written post! I am positively delighted to hear and read such articles and see things moving alongside natural processes rather than against them. Having read this post I have become even more curious, though. Is there another post on external signs of labour progress to be published soon? Would just so love to read it in such a clear and easy-to-understand language.

There is not another post yet… in the meantime you can follow some of the references/sources in the post and find out more. 🙂

Great article. I’m currently writing my dissertation on this topic.

What a great article, thank you! With a couple of my births I asked my midwife (a different midwife for the second birth) if they would do a VE to check my progress. Both refused saying there was no indication as labour appeared to be progressing well, and suggested if I wanted one I could do one myself. I did so, and found it great that I could take charge of this myself and it was a great way to connect me with what I was doing in labour. I feel on reflection that the midwives were transferring the power of the ‘external expert” back to the birthing woman (me).

Another excellent article Rachel. I love the quote “While a VE can provide information about how a woman has progressed so far in labour, it cannot predict how much longer you will be in labour…” and that there are “…other factors such as the strength, duration and length of contractions as well as a woman’s behaviour and wellbeing that can indicate progress in labour”.

I hope this enforces to women that they can refuse a VE. It is a shame that the language of the ‘caregiver’ can coerce a woman to accepting a VE that she does not want.

And midwives need to know that if they use coercion the ‘consent’ is not valid.

Thank you. I refused all VEs at my 2 homebirths as i didn’t see why they were necessary or helpful and i didn’t want to be ‘measured’ which would then turn centimetres into ‘progressing’ or ‘not progressing’ which in turn has negative connotations and can be disheartening to women if they fall into the second category.

They should not be a part of ‘normal’ procedures. Midwives need to go back to roots with other observation skills and a more intuitive presence – ideally!

Ugh I hate V E’s. In my 5 pregnancies I have had only 3. Two in my second pregnancy and one in my third pregnancy. I’ve been thrilled that I haven’t even been offered one during mytlast 2 births.I am very grateful for my, midwife. My husband and I are very hands off kind of people and so my midwife totally respects that and is hands off as well. We’ve had the same midwife for our last 3 births and she hasn’t caught any of the babies, she has encouraged my husband to do that. 🙂

love Love LOVE this article. One of my biggest pet peeves is this current trend to do prenatal cervical checks every week starting when the GBS testing is done. I encourage women to flat out refuse any prenatal checks and also discourage them during labor. Thanks for this post. #Sharing

Thanks :)… and I think antenatal VEs are an American thing (I’m guessing you are from the US). I’ve never seen it routinely done in the UK or Australia. A totally pointless and potentially dangerous intervention!

Question: as a nursing student pursuing midwifery, what do you suggest as a standardized tool/method for educating birth attendants about more accurately assessing birth progress without VE’s? Though I completely agree with your article, and I will take this with me into the field, there must be a standardized way of training birth attendants if this change away from VE’s is to be successful and adopted in birth facilities (like hospitals). Do you have any suggestions on further reading or material that would speak to this?

There is no accurate method for assessing labour progress (including VEs)… I think this is the main issue here. We need to acknowledge that assessment is individual, situational and develops with experience and attendance at births watching women birth uninterrupted. Even then – we will get it wrong. The human body cannot be standardised and a bodily process cannot accurately be predicted.

Duff (link in the post) created an alternative partogram that included assessment of maternal behaviour – so kind of a tool.

The midwife’s role is to assess the wellbeing of the mother, the wellbeing of the baby and the progress of labour. Our assessments will never be 100% accurate.

I teach midwifery students. The workshops about assessing labour include knitting (right brain) while listening to a woman in labour and then discussing where we think she is at based on her vocalisations… early labour, established labour, transition, expulsive phase or imminent birth. We talk about what is happening with hormones as labour progresses and what you would expect to see eg. effect of endorphin on behaviour etc. How the woman moves based on what is happening in her pelvis… where the baby is etc. It is complex and not necessarily accurate for every woman… but neither is a VE. I think we need to move away from the concept of standardised tools for individual women.

I would suggest reading Duff’s thesis. I will write a post about external assessment of labour progress in the near future as a follow on from this one 🙂

I will look forward to your post. I like the naming: External Assessment because it sounds professional and and convincing and sounds as if your forthcoming model will be useful and convincing in day to day practice.

I like your comment. This is such a good question. In practice if the pregnancy is low risk and remains low risk then in my opinion 4 hourly VE’s are definetly not necessary. I wonder if this question has been asked: Why do midwives and doctors want to do VE’s.it is a hard skill to learn , subjective, and it feels like if the findings from a VE differ between practitioners then one of the practitioners must be wrong. Too much emphasis is put on this skill as a measure of competence of the midwife . Our care must be individualised.

The reason midwives and doctors want to do VEs is about ‘authoritative knowledge’ and the historical influence of medicine which = the idea that separate parts of the body can be measured. It is why our midwifery text books are full of measurements of pelvises and fetal skulls (all bullshit – but authoritative knowledge). There is a genuine belief that VEs can determine progress… even in the face of research evidence and clinical experience. The paradigm is strong. The VE is an important skill for a midwife – in order to determine what is going on when external assessments of progress suggest there may be a problem (eg. to diagnose a brow presentation). This is why history (politics, culture and society) are vital subjects for midwifery students – so they can understand what they see playing out in the practice setting 🙂

Regarding VE’s, I’ll never forget asking my midwife (through group practice) if it was going to hurt when she told me she would come to my house and perform a VE in early labour. I was really worried, and she brushed it aside by saying, “oh, not it won’t really hurt, no”. I had a student midwife with me and she interrupted and told me that yes, sometimes they hurt, and I am allowed to say that I don’t want them. I will feel eternally grateful to that wonderful student!!

Now I am a student MW myself, and I’m wondering – what is the ‘norm’ for practice in homebirth settings as far as regular FHRs are concerned? I’ve always had real issues with the 15 minute intervals that are set in the hospital. Is it in the same boat as VE’s – we should offer, but women can safely decline? Or are 15 minutely FHRs (and after every contraction in second stage!) really necessary for the safety of the baby? I attended a birth last weekend and felt just awful reaching into the bath so regularly while the woman was completely relaxed and focusing inwards. I’d be interested to know what you think about this… Thanks! 🙂

Hi Bri

I wrote a short blog post about FHR http://midwifethinking.com/2010/07/29/listening-to-baby-during-labour/

Basically the timings are not evidence based and were/are created by a consensus of hospital-based practitioners. There is no consideration of the impact of continually interrupting and disturbing an instinctive process. The excessive fiddling about during pushing is particularly counterproductive… and not necessary for the safety of the baby. Most women I care for want the FHR to be taken – but for the assessment to fit around them ie. at a moment when it will be least disturbing. Or in response to a change or concern. 🙂

Thank you for your comment on my comment. Thank you for explaining this. In practice it certainly feels very authoritative . Making these issues explicit is just brilliant and will empower midwives and women to ‘work with each other’ to achieve sensitive care and safe care

I had three vaginal examinations in labour. I have really complex feeling about whether they were unhelpful or not. I certainly found them almost unbearable. I just couldn’t be still in labour – it felt absolutely impossible to lie on my back even for a minute. I was writhing around and found it so difficult. The first midwife wasn’t very kind either – she kept telling me to be still and turned on lots of lights and spoke really loudly, I felt in a safe place and she scared me. She said I was only just in established labour and that I wasn’t progressing and as I’d been labouring all night I would have to have syntocin if things didn’t pick up. I found this incredibly demoralising and upsetting at the time. However once the midwife left the room again, my partner and I together really changed how we were handling labour. I had been snoozy between contractions through the night and now I started standing up and swaying and working at being active. Throughout labour I could only bear contractions on my hands and knees so that didn’t change, but my behaviour between contractions really did. Within about 15 minutes I was very sick and contractions jumped up a huge step.

The midwives changed shift about three hours later and me new midwife gave me a vaginal exam as well.This midwife was much kinder and more understanding of my inability to be still, but she was trying to give the VE during the most intense part of my labour and never really got a very thorough feel .She said she though I was about 9cm. Shortly after this I began feeling really pushy. I had my thirsd VE after about 30 mins of pushing without the baby moving down. At this point the midwife thought I had a small cervical lip and advised me to use gas and air to help me control the urge to push for a bit. My pushing was completely reflex – telling me not to push was like telling me not to vomit! It was just not a possibility.

In some ways the VE I received shaped my labour and changed my behavious in some positive ways. But I’m not sure that a midwife taking a minute, being kind and reminding me how much I wanted to be active wouldn’t have been a better solution than what I actually had.

Thanks for sharing your experience. It sounds like you birthed despite the VEs rather than benefitting from them? Have you read this post: http://midwifethinking.com/2011/01/22/the-anterior-cervical-lip-how-to-ruin-a-perfectly-good-birth/

I hadn’t seen that article before – very interesting! I certainly couldn’t stop pushing once I started and didn’t really want gas and air very much (though once I had it I sucked on it hard enough). If I have another child, I’ll think I’ll try to be more consistent about refusing VE. I was so late (19 days when she was born) and felt rather desperate to avoid induction, I think I felt a bit confused. Also, as a primip, I wasn’t always sure what my sensations corresponded to. I don’t feel traumatised or upset by my VE, but I agree with your overall assessment that I continued to labour despite intervention rather than being helped. I would have loved a bit more midwife intervention in general though – through the night I was by myself with my partner having regular, intense contractions but only saw the midwife a few times between 1am and 7am. I didn’t really want her to do anything, but I would have liked some more reassurance and encouragement to keep moving.I found birth overwhelming and I sort of curled up at times rather than going with the sensations and I think a midwife could have helped me more during transition. As it was only about two hours from being told I was only just in labour to having all these contractions one on top of the other (I had several pairs with hardly any break in between – I remember saying ‘it’s just not fair, I should have a break’ over and over). I felt quite scared at that point that it would go on forever like that. Reassurance that I was progressing well rather than stuck with endless contractions would have been fabulous at that point.

You were missing midwifery care and reassurance… not intervention. You did a great job on your own unfortunately 🙁

sorry ladies. I am clearly going against the grain here with my experience. Several hours after being admitted to an induction ward in spontaneous labour (the only room at the inn) I was denied an examination by a very stroppy midwife. I ‘felt’ the need to push but she repeatedly told me I couldn’t possibly be at that stage. It was only when I was bent double in distress over a clinical waste bin and my husband spoke of going to the MIC, that she consented to check me over. She asked my husband to leave-unnecessarily-and then proclaimed that actually, yes I probably should be in the labour ward. She so hastily had to make the arrangements, that she forgot to let my husband back and it was only when I was wheeled past him that he knew I was being moved. I was then declined an epidural due to my advancement, but needed an emergency spinal due to the turn of events. I recall every midwifes name whom looked after me EXCEPT hers, however I could pick her face out of a lineup straight away. Due to her lack of willingness for a VE and her lack of belief in my own gut instincts, the trauma stays with me.

You are not going against the grain at all… if a woman requests a VE then the midwife should listen to her. It is a shame that you had to prove you were in labour by having one though, rather than the midwife just listening to you and moving you to the birth room. I am sorry that you were not respected by your midwife.

My first labour was so traumatic it’s taken me 4.5 years to brave getting pregnant again. The worst part was the VEs. I wanted to avoid them but as my waters had broken at 35+6 they made me feel I had no choice but to accept VEs to check for the baby’s sake. Even though surely they would be increasing infection risk! They kept forcing antibiotic tablets down me to avoid infection which I would immediately projectile vomit up causing me to be exhausted after 12hrs and 2 EXCRUCIATING VEs during which they did a stretch and sweep without telling me until afterwards. By the third VE I was screaming for the midwife to stop and had to actually kick her off me. She got annoyed and said she couldn’t tell how far along I was because I was ‘making such a fuss’ but I was around 8-10 so could start pushing…

Queue 1+hrs of pushing and what was apparently 8cm after all, no progression except swollen cervix and severe bruising on my son’s head. Not long afterwards they told me I was high risk for a c section so should have an epidural so I could be awake if I end up in theatre and that if I didn’t I’d have to have an emergency general anaesthetic. I unwillingly gave in and as I was sitting for the epidural I felt my son drop right down into the birth canal but they carried on…

Epidural failed despite 3 top ups and stalled my labour. After 2 hours of nothing it started up again (baby literally sitting at exit the whole time) and queue two hours of purple pushing on my back despite my protests at wanting to get on all fours and being told I couldn’t because I’d had an epidural (which hadn’t worked!).

At this point they called a Consultant to perform a ventouse delivery. They said if it doesn’t stick to the head within three attempts it’ll be forceps – I was screaming “I do not consent to forceps!” yet they said I would have no choice if ventouse didn’t stick… due bruised head it didn’t stick first two times but luckily stuck third time.

Before giving me a chance to push with the ventouse they said I HAD to have an episiotomy or I would tear ‘horrifically’… I said no… they then performed two, making an ‘I’ shape into a ‘Y’.

My son was born at exactly 36 weeks and had apgars of 9 and 10 despite the ordeal.

Suffice to say I was traumatised.

I’m now 18 weeks pregnant with my second and am planning a home birth with NO VEs!

I am so sorry that you suffered such abuse during your birth. I hope you are surrounded with respect and love (and no VE’s) for your next birth.

This is such valuable information to me as a new student midwife who has just experienced her first continuity birth. I found the midwife extremely pushy and very abrupt with the first time mum who knew little of what to excpect, along with myself. She asked the midwife several times to stop however to no avail. The above information has been so helpful for my future learning and practice and I thank the women who have replied openly and honestly, and can feel more confident in advocating for women in future.

It is awful that midwifery students must learn from watching bad practise and reflecting on it. Keep asking questions, and keep advocating for women… and keep the midwife you want to be in your vision.

I actually found the VE very useful during my labour, after having contractions at home for 3 days I was desperate to know what was happening! It was my first baby, I had no idea what labour felt like or what stage I was at, I didn’t know if I was about to push out a baby or whether I’d just started!! I went into my ML unit at Poole, they were lovely, reassuring, asked consent which I gladly gave, found out I was 3cm which was disappointing but at least I knew and that made me much more relaxed and I settled into proper labour much better knowing they could check what was happening. What I actually found more uncomfortable was the frequent US checks as it disturbed me out of my ‘zone’ so in the end asked for a bit longer between which was fine. I had a very long labour and ended up needing forceps and other intervention but all done calmly with informed consent- well done Poole!!!

I am a midwife working in a small rural hospital that offers continuity of care, waterbirth and homebirth. We are supported by 3 GP obs who are great support and very comfortable with the variance of normal birth. For many years, backed by our GPS we have had great leeway if Mum and baby were both well. However as protocols and policy have increased to control every aspect of our practice, the routine 4th hourly VE has become part of what we are supposed to “do”. It is very frustrating, and because we usually have a good and trusting relationship with our clients, when this policy is discussed and we explain that the policy states..”blah,blah…… but you have every right to refuse or decline , they say “whatever you think is best”. So I dont think it is best, I dont need to do routine VEs but must document that it was offered and refused??/ or not??? We have the tertiary hospital obstetricians closely scrutinising our practice and especially when a woman ends up being transferred if there has been any deviation from the policy we end up before the manager with “please explain”. Any tips??

Your situation is fairly universal ie. having policies that are not evidence-based or aligned with your philosophy… but having an ‘obligation’ to follow them (I’ve been there and done that!). All you can do is offer a VE as per policy (employment obligation), provide adequate information to gain consent (legal obligation), and make it very clear that this is her decision and you will support her either way (obligation to the woman). You can also reassure her that you think she is progressing well because x, y, z. If the woman says “whatever you think is best” – then say “it is not about me and I can’t make decisions for you… what would you like me to do? – you must make the decision”. It is very important that women take responsibility for their decisions (and the outcome of their decisions). As a midwife your responsibility is to provide information and support her decisions, not make the decision. You can tell your manager that she ‘declined’ a VE and you are unable to perform an assessment without consent. It is frustrating though. Perhaps some other readers will have some wisdom/tips for us 🙂

It is worth adding that Checking the cervix can result in artificial rupture of membranes, as was stated, but it was not mentioned that once in every 250 to 300 artificial rupture of membranes , the cord prolapses, which can result in fetal death or brain damage, as well as cesarean delivery. Cohain JS. The Less Studied Effects of Amniotomy J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(17):1687-90.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258375672_The_less_studied_effects_of_amniotomy?ev=prf_pub

Indeed – thanks for the article 🙂

Preach it! My birth plan (previously discussed and assented to by my midwives’ practice) said I did not want VEs unless medically necessary. Labor progressed rapidly after my water broke at home, and we got ourselves into the hospital but all our stuff, birth plan included, was in the car. The midwife on call could not meet us in triage; a hospital nurse insisted that I had to have a VE so she knew whether or not to get me a room. I consented (but not REALLY; I only felt I had no choice). It was so painful I said “Stop!” but she didn’t. So I screamed (no shame at this point, haha) “Get your hand out of me!!!” She did. She said, “I feel the baby’s head; let’s go.” Beforehand I felt very empowered and prepared, so looking back it still bothers me that I “allowed” something that was not right for me and that I think the nurse should have been flexible enough to see wasn’t necessary. It’s like they think when you come in bellowing with long, frequent contractions maybe you’re just being a diva…? I never heard anyone give a cervical number assessment but baby was born 2 hours later. 🙂

You can’t assert yourself when you are in full blown labour. It is very frustrating that the system requires a ‘number’ before admitting a clearly labouring woman. I was at a premature birth (34 weeks) a few years back. Mother obviously labouring strongly (third baby) – doctors examined her and told her she wasn’t in labour as her cervix was closed. He left the room – she birthed her baby 30 minutes later 🙂 There is more to birth than the cervix.

Similar story as the previous one. With our no.3 went to the hospital after “only” 30min of contractions… The look on midwife`s face who had to register us was – why are you ever bothering us coming here so soon? Having had two births behind I just knew these were transition/8-9cm/very-crazily-intense contractions… Surprise,surpirse – when she did a VE it was 10cm..

Oh if every woman could have their own midwife and not have to be subjected to that reception!

Thank you. I feel.sad too at my own experience of birth……can’t remember if I was asked for consent. Blood and maconium in waters when they broke…so induced but wasn’t told it could be normal overdue bowel movement of baby. anyway, emergency c section after final VE caused massive maconium and baby withdrew into womb…..so the one thing I’d say is has anyone asked what it may be like for the child to experience the other end of a VE? I feel so sad that it may have affected my son. He was showing no signs of distress apart from when syntocin went in and then VE. Thank you.

During labour we are so unbelievably compliant. I found VE’s intrusive, unnecessary and excruciatingly painful mainly because I was asked to lie down. On screaming and trying to climb away from the pain the midwife still continued to examine me. I am due to give birth again any day. In my birth plan I have said I will not lie down and will only give consent to essential VE’s.

It’s really important to know you can say no. I’m more clued up this time round!

What your midwife did to you is legally assault and battery. Will you have someone with you who can advocate for you in labour. You need to concentrate on giving birth – not on ensuring your wishes are respected.

Dear Kerry, You write that in labor women are incredibly compliant. But you are not in labor now, and you are anticipating a problem that you could resolve now by contracting with your midwife as to what you want. For you, vaginal exams are very painful and you dont want any. You can tell your care giver that vaginal exams are not for you, and you dont want any. I am a homebirth midwife and many women have made this request, which I respect. There is no reason that one has to have a vaginal exam against one’s will. There is no reason for vaginal exams if you are in good labor with regular contractions that hurt. If you are having regular contractions that are painful, then you are progressing. No reason to check. You just have to let the labor proceed by itself. Eventually you will have rectal pressure- that happens around 8 cm. Sometime after that, you will have the urge to push. It is true that some women have the urge to push before they are 10 cm and for some of those women, pushing is not effective and for some it is effective. I have had women for whom, without me pushing the lip of the cervix back during a vaginal exam during a contraction, the baby would not deliver- the head was stuck behind the lip. This never happens if the baby is 5 pounds, but sometimes happens when the baby weighs more than 8 pounds. I suggest you become more proactive NOW and not wait until labor to tell your caregiver what you need.

Has anyone been able to be successfully admitted to the hospital without them performing a VE? I suffered from PTSD due to the many checks with my firstborn. I only consented to one and I was coerced or just plain forced into the others. Some were in the midst of a contraction so that I wouldn’t be able to move away. This was on top going nearly hypertonic with pictocin and having to beg the nurse to lower the dosage. I have gotten my midwife to agree to no prenatal checks this time around and to not have any during labor but she is pretty stubborn about not admitting me without a check. Any advice?

I am guessing you are in the US? Pretty sure that the laws of consent apply in the US. No one can do anything to your body without your consent. If she refuses to admit you without a VE will she take responsibility of you birthing outside of the hospital?

recommend you deliver with someone who agrees to your demands. You are requesting that the midwife practice Evidence based midwifery. According to research -routine vaginal exams should be avoided because they sometimes cause artificial rupture of membranes and artificial rupture of membranes results in cord prolapse in 1 in 300 rupture of membranes as well as infections so are not evidence based or necessary except in the 2 situations I mentioned. Sounds to me, from my experience, that either you are having a confrontational relationship with the midwife you have selected and/or due to her lack of experience she is unable to accommodate you. It is a bad idea to give birth with a practitioner who you are fighting with. It is always possible to find someone who will provide you with evidence based practice. There is no reason for a vaginal exam on admission, because it is clear whether you are in good labor by watching how you act during contractions and taking a good history. Taking a good history and observing a woman for 30 minutes is enough to know if she is 1, 3 , about 5 or 10 centimeters dilated. I rarely need to do vaginal exams and many of the births I attend do not have a single vaginal exam.

If you absolutely cannot find anyone in the US, then come to Israel, and I will attend your birth. It wont be that convenient in some ways but it will be cheaper and you get a visit to the Holy land for same low price!

The 2 instances that vaginal exams are necessary in labor are

1. You and the midwife are not sure if the fetus is head down and ultrasound in unavailable to check it.

2. You have the urge to push, you have been pushing for an hour (or two) and the baby does not deliver and you want to be sure that the cervix is fully dilated.

I don’t see VEs done as often in the homebirth setting – but even so, if a woman begins asking about whether she’s complete I always encourage her to check for herself! Even the most hands off midwives feel compelled to check and see if a mom is “ready” to push. It’s a hard habit to break!

I actually chose to deliver at the hospital I did because they advertised that the philosophy of care was as little intervention as necessary and minimal VE’s. This proved true with my first birth under a midwife’s care. However, my second delivery happened during hospital hours that were covered by OB’s. My baby’s position made VE’s excruciating and yet I had 4 in 9 hours of care 3 of them during 5 hours of active labor. I still get ill thinking about it and have had nightmares and panic attacks related to the experience. I’m hoping to ask my husband to advocate for me in my next delivery for no VE’s but fear that the simple anticipation of it will create anxiety at my next birth.

I sorry that you were traumatised by your birth experience. Can you meet with your care providers to discuss your fears and make sure that everyone is clear that you will not be having VEs? If you have a written plan of care (ie. no VEs) in your hospital notes it will be easier for your husband to advocate for you.

I spent many years thinking that the woman who were traumatized by this and that were exaggerating. I am 60 years old. I just had a really traumatizing experience with nurses. My husband and my mother think i am exaggerating. Think whatever you want, the last thing on earth that i would do would be to confront the nurses who hurt me so badly. I will slowly heal, but i will continue to make sure I dont bump into them ever again, in any situation. So, i find the above advice not good advice for anyone who is traumatized. I know I was traumatized because i am a normal person, but after the trauma, i slept alot and i every time I thought about it, i felt really bad.

We all deal with trauma differently. We need to do what helps us heal. I have known many women who have gained a sense of healing from having their experience acknowledged by the people who caused the trauma… and knowing that the person/s will not do this again. As you point out – care providers often do not realise the effect they have.

I deliver most of my births without any vaginal exams. There is rarely a reason to do one. The reason not to do them is that they push bacteria towards the baby and sometimes cause the sac to break. You are welcome to deliver with me in Israel. It’s $500 for the birth package. An apartment to rent in Israel is $250 per month where i live. You have options!

I truly could not even read this topic much less comment on it until now. My first child was born in 2013 and, after what I thought was the “requisite” PAP smear and VE with an OBGYN, I decided that was utterly dehumanizing and I sought the care of a midwife. At my meet and greet I told her unequivocally that I was never doing that again. She assured me she would respect me and my rights to my own body. Haha…I actually feel stupid writing that. Even now, I am so ashamed of my gullibility. I believed her. I was then 13 weeks pregnant. At 41 weeks, my water broke at home and my contractions started. She demanded I come in to her office. I refused, saying I was in labor, and I needed to stay home and rest. She said I “had to,” but if I wanted to, I could labor in a hotel in town until I was in active labor and could get admitted. (Would you want to be the guy in the room next to a woman in labor? What kind of midwife tells a patient to labor at the Holiday Inn, anyway?) That should have been a clue. I traveled to her office and, like night and day, the mask dropped and she demanded a cervical exam. I refused again and again. She called in her Director. I argued with the Director for five minutes, standing in front of her, amniotic fluid leaking between my legs, staving off contractions because I was so scared and outraged. In the end, she was utterly inflexible and insisted that I would “do it or you can’t have your baby here.” She was going to kick me out of her midwife practice IN LABOR if I didn’t spread my legs and give her access to measure my cervix whenever she wanted. Way too late to line up another midwife or OBGYN, what choice did I have? Of course, by the end, they had done so many cervical exams they demanded I have a cesarean because they could have introduced bacteria into me and I could have an infection. I refused the c-sec and they disconnected the pitocin because I was now proceeding with a vaginal birth against medical advice. The midwife made me write my own waiver (yes, in labor, she made me dictate a legal waiver of responsibility and sign it). After being repeatedly violated, assaulted, belittled, threatened, and coerced and felt helpless and hopeless. I relented to the c-section. The midwife’s response? “I know. We’re already prepping the room.” I tried so hard for months to get over it but I couldn’t. Even now, two and a half years later, I cannot get over the PTSD and my shame for trusting these midwives. I complained to the Dept. of Public Health and first nurse screamed at me that it seems the problem is with me and they “have to do those exams and you have to let them and as long as you have a healthy baby you don’t get to complain!” Weeks later I called to follow up on the investigation and it became clear they hadn’t even opened one. I had to contact my State Representative to even get them to investigate this. The Supervising nurse called me out of the blue one day to tell me they investigated and found nothing illegal. The midwives and director acknowledged to her that I refused the exams and that they threatened to kick me out IN LABOR but “that’s not illegal.” So…not sure where that leaves women’s rights to their own bodies. Apparently, we have none.

I am so sorry that you were assaulted and abused during your labour. You have nothing to be shameful for – you are not to blame for trusting your midwife. Your care providers are to blame. It is illegal to do anything to someone else’s body without consent. Whilst this may be ‘normal’ in that health care facility it is against the law ie. is not ‘consent’. I admire your bravery – trying to get this investigated. The tide is turning… women are beginning to be listened to. Did you see this: https://www.yahoo.com/news/woman-sues-hospital-for-traumatic-birth-that-201605478.html?ref=gs ? I am currently writing up a research article about women’s experience of traumatic ‘care’. I hope you are getting some help to process the emotional and psychological impact of your horrific experience.

HI Rachel.

Thanks for another fascinating article. I had never heard of the Rhombus of Michaelis so intrigued I clicked on the link which only went to Sara’s generic page of articles. After a search I found the direct link, so here it is if you’d like to update your hyperlink: http://sarawickham.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/tpm8-the-rhombus-of-michaelis.pdf

Thanks. Virginia.

Hi Virgina

I’m pleased you liked the post 🙂 I have deliberately linked to Sara’s page/list rather than directly to the pdf. I’m not sure of the copyright situation re. direct links to pdfs. Also, in terms of measuring website ‘traffic’, it is best that readers access the article via Sara’s website. ‘Traffic’ data collection can be important for writers who want to monitor how readers access and use their work… and for generating revenue in some cases. 🙂

Oh sorry about that. I thought it was unintentional. As you were… 😉

Clearly this post is old, but I experienced great trauma at the hands of the nurses who insisted on doing insanely painful vaginal exams. I’m a survivor of sexual assault and I can’t think of much about my horrendous birth experience that was more traumatizing. The lack of knowledge and understanding of how this “best practice” effects women is revolting. I’m now pregnant with my second child and will refuse all routine vaginal exams. If a doctor, midwife, or nurse can’t provide some amazing reason for having one it simply won’t be happening. I wish more medical professionals had your view of it. I’ve completely ruled out providers based on the idea that I WOULD have to have a vaginal exam when I showed up in labor. To me this underlines the idea that they do not understand informed consent or the unique needs of every woman even if operating under the headline of a midwife based model of care. It simply amazes me that when we look at how many women have experienced sexual assault the medical community isn’t more aware or sensitive to the women who have experienced it. Not that only women who have experienced assault experience PTSD after vaginal exams. I think either way my experience would have been difficult to get over. Thank you for your informative Arne supportive post.

Hi Danielle, Excellent name! 🙂 Extra points if you’re a Libra!! I have not suffered sexual assault (except at the hands of my midwives and doctors while in labor) but I found the forced vaginal exams traumatic. Maybe because I was threatened and even the idea that I might have a choice in the matter was taken from me. Oh yeah, and because they were completely unnecessary, discouraging, and were later used to justify an unnecessarian (i.e. “we’ve done so many exams we could have introduced bacteria and you might have an infection. She’s not in distress – yet – but need to get that baby out now!”). I completely agree with your post and I support you!! I am concerned about you, though. I also made it clear at my meet and greet that I was not going to consent to any vaginal exam and my midwives also assured me they would never push me to do anything I didnt want. Until I actually went into labor I felt very comfortable with these women. I dont have to tell you that once you are in labor, sadly, many providers drop any pretense of respecting your wishes and all of a sudden, it’s, “hospital policy dictates you will have an exam upon admission and every 2 hours or as needed…” etc. Unfortunately, you will need a strong support plan. Have you discussed this with your laboring partner? Is he/she 100% in agreement with you? Are they wiling to support you and take a stand when your doctor tells you they wont admit you until they are sure you’re at least dilated 6cm? What about when they try to play chicken and let you labor in the waiting room without admitting you until you “consent” to an exam? How about when you’ve been laboring ten hours and the doctor tells you she needs to know your progress and what position the baby is in because the baby “might” be in danger? Is your partner strong enough and supportive enough to reassert your position on these exams and remind the doctor that he/she promised they wouldnt force you? Is your partner willing and able to cut through the bullshit and argue for you in the face of overwhelming bullying, threatening, harassment, coercion? If so, I envy your life decisions because you have chosen a partner well. 🙂 My partner was overwhelmed by seeing me in labor and just wanted it all over and did not support me. You never really know until you’re in that situation so I strongly recommend having an emergency plan. There are some very helpful websites that provide an emergency call number for women who are being mistreated in labor. When my cousin went into labor, I printed out this websites info, including the emergency call number. I put it with a printout of the law in her state regarding women’s rights in labor (e.g. right to informed consent which really means RIGHT TO SAY NO to any exam or procedure, right to be free from harassment, right to birth in a position of your choosing, right to have your chosen partner by your side), and I also gave her my telephone number because I WILL BE HER ADVOCATE. Thankfully, her labor went smoothly but I cannot stress enough the importance of having a strong partner by your side and the emergency call number saved in your phone. If you are very concerned, you might get the number of a supportive attorney you can call if the situation arises. At the very least, keep your phone with you and ensure your partner has theirs, too. If/when your providers start threatening you, pull it out and start recording. It has a very quietening effect. (You are creating a record of harassment – hopefully that will get it to stop at that moment but if not, you always can play it for the medical malpractice insurance company and jury). Sorry to go on and on. It’s just that I was in your shoes three years ago and while I do hope your doctors keep their word to you, mine did not and I’m afraid you’re in for a battle of wills, while in labor. I dont want you to go through the same PTSD, fear, dread, trauma, feelings that you’re less than human, not worthy of being treated humanely, that I did. The consequences of being violated in labor are very real and very, very dark. I think that if I had chosen a birth partner better and been more prepared I wouldnt have suffered what I did and I wouldnt have missed so much of my first year of motherhood. My baby deserved my full attention and I should have felt love and joy at this time, not stepping away to cry in the bathroom. Best of luck to you. Hugs and God Bless!!!

The head accommodates the pelvis: See

Cohain JS. Three cases of Prolonged Second Stage of Labor 14, 17 and 24 hours. Midwifery Today 122:18-20.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1zM_aY2An1sICUIP12Gwn0b5gSP4Kzlg7HP

Yes… but the cervix accommodates the head in terms of how far it opens. It stretches over the baby’s head and the head (skull bones) mould to fit the pelvis 🙂

I found the VEs very uncomfortable, painful in fact. I was in labour with contractions coming every 5 mins and was managing them with breathing and leaning against a wall or my partner. Being asked to lie down to undergo the VE made the contractions harder to cope with. I asked the midwife if she could examine me with me standing up but she said she couldn’t. In the end she could not find my cervix, so I was offered gas and air which helped me relax enough for her to examine me (I was not dilated at all). Unfortunately this meant I could not be admitted to the midwife led birth unit as you have to be 5 cm dilated before they’ll admit you (so I do wonder what would happen if you refused VEs but wanted to birth in the MLU). Other reasons (being sick throughout my labour and worries about the baby’s heart rate) meant I went to hospital for the birth and each of the VEs was as uncomfortable but I knew to take gas and air so that helped. The worst thing was having to lie down for them (and for various other monitors to be applied) as that made the contractions really painful. I did manage to insist on standing up as much as possible despite all the monitors and wires. I would prefer not to have VEs, but it’s hard to stand your ground when you’re being told that they need to do something! I have to say,the midwives tried to be as gentle as possible, whereas the consultant was less gentle.

Incidentally, I also find smear tests really painful/uncomfortable and the (usually very patient and understanding) nurse has trouble finding my cervix.

A really interesting article!

This is such an interesting read. And empowering for me. During my last (first) labour I was routinely examined. After 12 hours of labour at home and having no experience of birthing I was keen to know how things were going. Unfortunately I have a very friable cervix. As soon as MW had completed the VE (3cm – very favourable cervix) I bled all over the place. I was due to give birth in a Midwife led unit as I was a low risk pregnancy. Due to the bleed I was sent to a labour ward, routinely checked every few hours, waters broken, slow progress, put on a drip to speed me up ended up with an epidural (after doing 24 hours with no pain relief!) and finally an EMCS after getting to 8cm in 34 hours and the

Conclusion being that baby wasn’t facing favourably to open my cervix adequately. I no longer believe I needed this section and that without the first BE and the bleed I might have avoided the whole catalogue of interventions. I will be 1) staying at home for as long as possible next time and 2) not having VEs unless there is a medical reason to have one. Thanks for this article.

I am sorry that you birth was sabotaged. A cervix will open regardless of the position of the baby (even if the baby is transverse or not on the cervix)… it just opens at a different pace/pattern. It sounds like your baby was occipito-posterior – a normal and very common variation: https://midwifethinking.com/2016/06/08/in-celebration-of-the-op-baby/

Having routine vaginal exams is not part of a physiological birth nor the Midwifery Model of Care. It is the medical model . Rarely, a vaginal exam is indicated, but not routinely!

No, they shouldn’t be… but lots of midwives, even in midwifery group practices use them routinely to assess progress. Unfortunately midwifery is often very medical.

Then they are medwives, practicing the medical model, not the Midwifery Model! THEY are who nis giving midwifery a bad rap! Hire a true midwife!

I agree… but there seem to be more of them than us at the moment – certainly in Australia. They argue that midwives who are not medical are dangerous and give them a bad rap. And over here half of the private practice midwives have left private practice due to the medical regulation of their practice and vexatious reporting. So women often can’t hire a true midwife 🙁

Sadly, the same is true here in the USA! Most Medwives deliver in hospitals, most true midwives deliver at home, though there is some cross over. But the overwhelming majority deliver in hospital, so women think all midwives are like that. 🙁

.

We all know that women who have a BBA (born before arrival) or “freebirth” or labour with carers who understand and support the hormonal physiology of labour and birth most often have no Vaginal Examinations The latter usually observe for signs of progress as you describe above but also know that disturbing a labouring woman to do a VE or anything requiring conscious efforts can slow and even stop her labour. Please when next you revisit this and similar blogs can you incorporate research about labour hormones, their origins and influences?/

https://midwifethinking.com/2017/02/03/understanding-and-assessing-labour-progress/

Hi, I had very traumatic birth experience by a midwife who did this my entire birth to speed up the baby‘s arrival. My baby was in no rush to get out, she forced me to labor when I wanted to go to the hospital. And I am still scarred from it, can you email me? I am wondering if I can walk through it and get advice if I need to report it. It was in a small clinic..

I am so sorry that you experience such traumatic ‘care’. I can’t provide individual advice or get involved in individual cases. I’m not sure where you are based. I suggest connecting in with some support re. working through your experience and reporting it too. Some organisations include

– Australia: Birth Talk: http://birthtalk.org/

– UK: AIMs: https://www.aims.org.uk/

I’m not sure re. other countries. Hopefully some readers will add organisations. You could also contact a maternity consumer group for direction. I hope you find the support you need and deserve. What happened to you is not OK x

If you live in the U.S., you should notify your State’s Department of Public Health. Just google: [your state, ex. Delaware] Dept of Public Health, then navigate to File a Complaint. Some of them have forms to fill out online and submit (print a copy of your Complaint + the confirmation page), some of them have an address to mail your Complaint to (keep a copy of the Complaint + get a USPS tracking number), and some cant be bothered and only have a telephone number to call (record this call – they are, so you can, too). Be as specific as you can in your Complaint. Include the facility name, address, date of the incident, names of all doctors, midwives, nurses and witnesses, describe the incident in as much detail as you can and specify WHY you have a problem with it (i.e. this is harassment, they threatened me with —, this is coercion, this is medical rape, etc.). You may need to follow up every week to get some movement. Being very Dr-friendly, they arent interested in helping you under the best of circumstances and they may hide behind everything’s-slow-now-due-to-CV19 excuse. Hold their feet to the fire. They dragged their feet so long on investigating my Complaint that I asked my State Representative for help just getting them to look into it. DON’T GIVE UP. Remember, you’re doing this for your daughter! (And mine…and yours, if you’re reading this!)