Updated: November 2023

I have written this blog post in response to readers’ requests. Trying to make sense of the research and guidelines hurt my brain, and I almost gave up a few times. So, for those who asked – I hope this post meets your expectations! The post explores blood glucose levels (BGLs) in pregnancy, and attempts to make some sense of the fairly nonsense diagnosis and management of ‘gestational diabetes’ (GD). This post is not about Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, and I am assuming you already know about the relationship between blood glucose (sugar) and insulin – if not do some googling.

Blood glucose and insulin in a healthy pregnancy

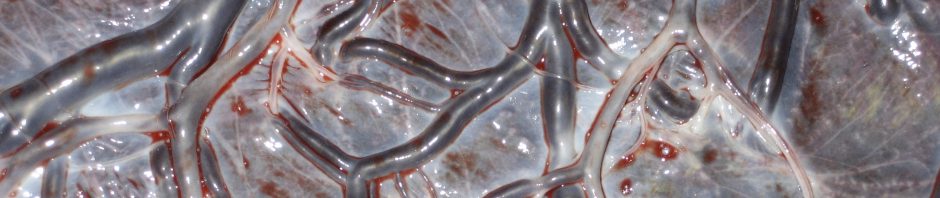

Babies needs glucose to grow, and the demand for glucose increases as pregnancy progresses and the baby develops. From around 20 weeks, placental hormones cause insulin resistance in the mother’s cells. Insulin resistant cells are less able to convert glucose into energy, resulting in a peak of blood glucose after eating a meal which goes through the placenta to ‘feed’ the baby. In response to this peak, the woman’s pancreas increases the production of insulin to bring BGLs back down to a healthy pre-meal range. So, during pregnancy the woman’s body needs to bump up insulin production to counteract the effect of insulin resistant cells. Once the baby is born, the placental hormones stop entering the woman’s circulation and her insulin metabolism returns to her pre-pregnant state.

High blood glucose in pregnancy

[NOTE: the clear as mud definition of ‘high’ is discussed below in ‘parameters of normal’]

Some women’s bodies are unable to produce the additional insulin required during pregnancy. This results in high levels of glucose remaining in the blood instead of being converted into energy by insulin. The exact cause of this situation is not clear. However, pregnancy places additional demands on the body’s metabolism, and pre-existing health issues influence the ability of the body to meet these demands. High BGLs in pregnancy are associated with an increased chance of health problems during pregnancy (eg. pre-eclampsia) and later in life (eg. cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes). Therefore, pregnancy may offer a glimpse into the general health of a woman, and her ability to meet physical challenges. Rather than causing ill health, abnormal BGLs may reflect underlying ill health.

What is known is that high maternal BGLs influence the development of the baby. In early pregnancy (before 14 weeks) high BGLs are associated with an increased chance of miscarriage, congenital abnormality and subsequent stillbirth (Murphy et al. 2017). This is because the structural development of the major organs is taking place at this time, and any toxin, including excessive glucose can cause damage. However, BGLs are only high in early pregnancy in poorly controlled, pre-existing diabetes.

In contrast, ‘pregnancy induced’ high BGLs do not occur until after 20 weeks when insulin resistance kicks in. By 20 weeks all of the baby’s major organs have formed, and the baby grows mostly in size rather than in complexity. Therefore, pregnancy induced high BGLs primarily effect the weight/shape of the baby. In response to maternal high BGLs passing through the placenta, the baby increases their own insulin production. This insulin converts the excess blood glucose into additional fat stores resulting in a heavier baby. This extra fat is concentrated around the baby’s upper body, in particular around the shoulders. Chunky shoulders increase the chance of shoulder dystocia and perineal tearing during birth. Insulin can also delay the production of surfactant, which prepares the lungs for breathing. This can cause breathing issues at birth, particularly if the baby is born early (eg. by early induction or c-section – which are more common when GD is diagnosed).

Once the baby is born, they no longer need to produce high insulin. However, adjusting and re-balancing insulin and BGLs can be a bit of a bumpy ride for the baby. The withdrawal of high BGLs is sudden (as soon as the placenta stops functioning); but it can take some hours before the baby’s insulin levels drop. During this time the high insulin can covert too much of the baby’s blood glucose into energy resulting in low BGLs (hypoglycaemia).

The baby’s high insulin levels during pregnancy also increase their red blood cells. After birth the baby needs to break down and excrete these additional red blood cells. A by-product of breaking down red blood cells is bilirubin. If there is a lag between breaking down the red blood cells and excreting them out of the body, bilirubin builds up causing jaundice. Jaundice is common in babies who produced high insulin in the uterus.

The effects of high BGLs and high insulin in utero may also cause long term epigenetic changes to the baby’s metabolism. These babies have an increased chance of developing obesity and Type 2 diabetes later in life.

If you want a more in-depth explanation watch this movie:

In summary high BGLs in pregnancy are not ideal, and can alter the growth and development of the baby.

‘Gestational Diabetes’

In an attempt to identify and manage women with high BGLs, the maternity system has defined a disease and created a label that clinical guidelines can be based around. When high BGLs are identified for the first time during a pregnancy it is referred to as ‘gestational diabetes’ (GD) or ‘gestational diabetes mellitus’ (GDM). Most cases of GD are pregnancy induced ie. caused by an inability to meet the additional insulin needs of pregnancy – as described above. Occasionally, Type 2 diabetes was already present but only identified in pregnancy. Either way – high BGLs will be termed GD until proven otherwise ie. after pregnancy when BGLs fail to return to normal in the case of undiagnosed Type 2.

However, due to inconsistencies in who is tested, and how and what parameters are applied, there is a huge variation in whether an individual woman gets diagnosed and labelled with GD or not. For example, the incidence of GD varies globally from 2% to 26% depending on the definition used, the approach to screening, and the population of women tested.

Applying the label

There are two main approaches to screening for GD – universal screening (every woman is offered a test) and risk factor-based (only women with an increased chance of developing GD are offered a test). There is no evidence to demonstrate that either approach improves outcomes for mothers and babies. A Cochrane Review concluded: “There is not enough evidence to guide us on effects of screening for GDM based on different risk profiles or settings on outcomes for women and their babies… Low-quality evidence suggests universal screening compared with risk factor-based screening leads to more women being diagnosed with GDM.”

TYPES OF TESTING

The Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) is offered between 24 and 28 weeks gestation, or earlier for women considered ‘at risk’ of GD. It is the standard recommended test for GD diagnosis in most clinical guidelines worldwide. It involves fasting overnight, then drinking a glucose solution, followed by a blood test to assess BGLs. The dose of glucose can vary from 50g, 75g to 100g; and the timing of the blood test varies from 1 hour, 2 hours or 3 hours afterwards. There is no evidence to support any of these variations, however most guidelines recommend 75g of glucose and a 2 hour blood test. The OGTT assesses how well a woman’s body responds to a huge bolus of glucose (and chemicals – read the label).

The Glucose Challenge Test (GCT) was previously recommended as a screening assessment (24-28 weeks) to determine which women went on the have the OGTT. The test involves drinking a 50g glucose solution and having a blood test 1 hour later. However, the test lacks both sensitivity and specificity and is no longer recommended (except in the US).

The Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is only recommended for identifying pre-existing diabetes during the first trimester of pregnancy. The results of the blood test provide an indication of what the average BGLs have been over a 2-3 month period. This test cannot effectively identify pregnancy induced diabetes – only previously undiagnosed Type 2 diabetes.

Self testing is not recommended in any guidelines – however some women choose to do this rather than an OGTT. The woman tests her own BGLs over a few days to get an idea about what her BGLs are doing when she is following her usual diet and lifestyle.

PARAMETERS OF NORMAL

It is generally agreed that the normal range of blood glucose for non-pregnant people is 4.0 to 6.0 mmol/L (millimoles per litre) when fasting, and up to 7.8 mmol/L two hours after eating. Diagnosis of non-pregnant diabetes occurs when an OGTT identifies fasting BGLs ≥ 7 mmol/L or BGLs ≥ 11.1 two hours after 75g glucose.

However, when it comes to pregnancy, definitions and parameters of normal are not so clear. Various organisations advocate differing diagnostic parameters, and Bonventura, Ernest & Dee (2015) describe a number of them. However, I’ll stick to the most commonly used criteria initiated by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG). In 2010 the IADPSG Consensus Panel lowered the threshold for GD diagnosis. This move was based on the findings of one study – the HAPO study. This was an observational study looking at the risk of ‘adverse outcomes’ (see above) associated with 7 different categories of fasting BGLs; and with 1 hour and 2 hour BGLs after 75g glucose. The findings identified an association between fasting BGLs and the frequency of particular ‘adverse outcomes’ (see association vs causation in this post). The study reported: “frequencies in the lowest and highest [of the 7 fasting BGL] categories, respectively, were 5.3% and 26.3% for birth weight above the 90th percentile, 13.3% and 27.9% for primary [first ie. not VBAC] cesarean section, 2.1% and 4.6% for clinical neonatal hypoglycemia [low BGL], and 3.7% and 32.4% for C-peptide level [which reflects baby’s insulin levels] above the 90th percentile .” The amount that the 1 hour and 2 hour BGLs went up also influenced the frequency of ‘adverse outcomes’ – although the associations for primary c-section and neonatal hypoglycaemia (low BGLs) were weak.

The IADPSG Consensus Panel concluded that: “because associations were continuous with no obvious thresholds at which risks increased… a consensus was required to translate these results into clinical practice.” And so the new GD diagnostic threshold was created: OGTT results of BGL ≥ 5.1 mmol/l fasting or ≥ 8.5 mmol/l two hours after 75g glucose load. These thresholds are based on the average BGL values that increased the odds of a big baby by 1.75 times. Whilst this threshold may reduce the rates of babies over 4kg, there is no evidence that it will reduce the rate of birth/newborn complications Bonventura, Ernest & Dee (2015).

WHO changed their recommendations to align with IADPSG’s. WHO even state in the recommendation that the quality of evidence to support this new threshold is ‘very low’, and the strength of the recommendation is ‘weak’. This threshold results in up to 16% of pregnant women meeting the criteria for GD (previously 5%). Kevat et al. (2014) raised a number of concerns about the impact of the lower threshold for Australian women – many of which can be applied to other populations. However, despite an initial wave of concern from care providers, consumers, maternity organisations and researchers – these new thresholds made it into clinical guidelines and practice worldwide.

Research carried out after the implementation of a lower BGL threshold demonstrates no improvements, quite the opposite. A Cochrane review looked at ‘different intensities of glycaemic control’ for women with GDM. They found that with lower BGL targets there was no difference in the rates of c-section, induction of labour or body fat percentage of the baby. However, there was an increased risk of the women developing high blood pressure and protein in the urine. The review concludes that: There remains limited evidence regarding the benefit of different glycaemic targets for women with GDM to minimise adverse effects on maternal and infant health. Glycaemic target recommendations from international professional organisations vary widely and are currently reliant on consensus given the lack of high-certainty evidence.

Two Australian studies investigated the benefits and harms of lower BGL thresholds for GDM. The first study (Cade et al. 2018) examined the impact of introducing the new thresholds and found that: “There was an increase in annual incidence of GDM of 74% without overall improvements in primary health outcomes. This incurred a net cost increase of AUD$560 093. Babies of women with GDM had lower rates of neonatal hypoglycaemia and special care nursery admissions after the change, suggesting a milder spectrum of disease.” The latest Australian study (Hegerty & Ostini 2023) compared two large retrospective cohorts, one before the BGL threshold changed (2011-2013) and one after the change (2016-2018). The rate of GDM diagnosis increased from 7.8% to 14.3% between the cohorts. For the cohort with lower BGL thresholds, there was no improvement in the rate of shoulder dystocia, c-sections or hypertensive disorders. Instead, there was an increased rate of planned birth (induction or c-section with no labour) from 62.9% to 71.8% and planned early birth (before 39 weeks) from 35% to 45%. These rates were even higher for women prescribed insulin. Early planned birth is important to consider in relation to short and long-term newborn health and breastfeeding. For women diagnosed with GDM the chance of going into spontaneous labour and giving birth vaginally (SLVB) went from 30.01% to 23.6% between the two cohorts. Note that I can’t work out from the article if ‘vaginal birth’ includes an instrumental birth or if this ‘spontaneous labour’ includes augmentation. However, I think it is safe to say that physiological birth is likely to be very uncommon for women diagnosed with GDM. The researchers conclude that: Outcomes were not apparently improved with increased GDM diagnosis. The merits of increased IOL or decreased IOL or decreased SLVB depend on the views of individual women, but categorising more pregnancies as abnormal, and exposing more babies to the potential effects of early birth, medication effects and growth limitation may be harmful.

Increasing calls for a review of the diagnostic criteria (from medicine) are being ignored as the new threshold norm continues (Bilous et al. 2021; Doust et al. 2022).

Treating the label

Once a woman has been labelled with GD she is usually diverted into ‘GD-centred’ antenatal care. There is often stigma attached to having GD, and additional medical surveillance and restricted choices regarding birth setting. Management of GD centres on keeping the BGLs within a certain range via diet and exercise, and/or insulin medication. The issues around dietary recommendations are a whole other issue that I can’t fit into this blog post. Long story short – the usual GD recommendations involve a high carb (ie. sugar) diet. Alternatively, Lily Nichols has written a couple of great books about diet in pregnancy and for GD (see below in further resources).

Although there are varying opinions about what BGLs should be maintained by women diagnosed with GD (Bonventura, Ernest & Dee (2015). In general the fasting BGL target is around 5.0-5.5 mmol/l fasting and the 2 hour post meal BGL is 6.7-7.1 mmol/l (by capillary blood, ie. finger prick test). Not surprisingly, hypoglycaemia (low BGLs) is a common problem for women trying to keep their BGLs within this range.

WHO summarised the evidence into the effectiveness of GD treatment. The only outcome categorised as ‘high quality’ is that treatment for GD reduces the chance of having a baby 4kg+ (number needed to treat NNT = 11.4 to prevent 1 large baby). However, the evidence indicating a reduction in shoulder dystocia is of ‘low quality’ (NNT = 48.8 to prevent one shoulder dystocia). There is ‘moderate quality’ evidence that treatment reduces the chance of hypertension (NNT 18.1) and pre-eclampsia (NNT 21). For all other outcomes evidence was ‘moderate’ to ‘low’ quality. Bear in mind the research in the WHO summary was carried out before the new lower GD thresholds were introduced. A more recent Cochrane Review compared lifestyle interventions (diet and exercise) with ‘usual’ care or another intervention and found no difference in any outcomes except the size of the baby.

It is also important to note that only 14-22% of women diagnosed with GDM will have a baby over 4kg and ultrasound assessment of size is ineffective.

Labour and birth care for women labelled GD

The IADPSG Consensus Panel acknowledged that the “bias of caregivers toward expectation of adverse outcomes may increase morbidity due to increased intervention” for women diagnosed with GD. Women are often coerced into early induction of labour or even c-section because they have been diagnosed with GD. By coerced, I mean they are advised to have an intervention, rather than discussing the risks and benefits of various options, and their individual situation, then making their own decision.

Large-scale research exploring birth outcomes for GD tends to focus on the label rather than on BGLs. This results in 3 groups of women being mixed into the research sample:

- women with pre-existing diabetes only diagnosed in pregnancy

- women diagnosed with GD who had high BGLs during pregnancy

- women diagnosed with GD who maintained normal BGLs during pregnancy

For this mixed up group of GD women a Cochrane Review concluded: “There is insufficient evidence to clearly identify if there are differences in health outcomes for women with gestational diabetes and their babies when elective birth is undertaken compared to waiting for labour to start spontaneously or until 41 weeks’ gestation if all is well.” (the ’41 weeks’ is because induction at this gestation tends to be standard for all women).

However, things look different when we consider women based on what their BGLs have been in pregnancy rather than their GD label. In this case there are 2 distinct groups:

1. Women with normal BGLs (and a GD label)

These women do not have babies effected by high BGLs – because they didn’t have consistently high BGLs during pregnancy. Their babies are as likely to be over 4kg as women without GD. They should be cared for in the same way as women without a GD label because their ‘risk profile’ is the same. For this group of women induction is not supported by evidence or clinical guidelines. ACOG (US) state that “women with GDM with good glycemic control and no other complications are commonly managed expectantly until term.” Queensland Health (Australia) recommend that if blood glucose is well managed, there is no indication for induction for gestational diabetes. Despite this clear guidance women, are often booked in for an early induction by their care provider based simply on their GD label.

2. Women with abnormal BGLs (and a GD label)

This group of women are at increased chance of experiencing complications associated with high BGLs during pregnancy (see above). However, even for this group of women there is a lack of evidence to support induction. A paper by Berger and Melamed (2014) discusses the research relating to the timing of birth for women with GD, including the risks of induction for women and babies with GD. Like the Cochrane review above, they found inadequate evidence to support induction of labour for women with GD and concluded that “until such data are available, the clinician should consider the maternal, fetal and neonatal implications of induction of labour versus expectant management, involve the patient in the decision process and as usual follow the maxim of ‘‘first do no harm.’’

The main concern regarding high BGLs in pregnancy is the size of the baby (see above). This is often used as the reason for recommending induction. Babies with big shoulders are more likely to experience shoulder dystocia. For example, in non-GD pregnancies, shoulder dystocia occurs with around 1% of babies weighing less than 4kg compared to 5-9% of babies weighing over 4kg (Politi et al. 2010). These figures may be higher for babies subjected to high BGL in pregnancy because of the distribution of their additional weight (ie. upper body and shoulders). However, increased shoulder dystocia rates may also be partially due to the interventions women with suspected big babies experience. For example, if a care provider suspects a ‘big baby’ the woman is more likely to experience interventions (syntocinon, c-section, instrumental birth, etc) and complications regardless of whether her baby is actually big (Sadeh-Mestechkin et al. 2008; Blackwell et al. 2009).

Not surprisingly, induction before 40 weeks does reduce the chance of shoulder dystocia. A baby will be smaller before 40 weeks than after 40 week, and therefore statistically less likely to get stuck. A Cochrane Review comparing induction of labour before 40 weeks for a suspected big baby with waiting for spontaneous labour, found that induction decreased the incidence of shoulder dystocia from 6.8% to 4.1%. However, they also found an increased rate of severe perineal tearing in the induction group of 2.6% vs 0.7% in the spontaneous labour group; and an increase in the treatment of jaundice for the baby (11% vs 7%). Both NICE guidelines and WHO guidelines state that induction of labour should not be carried out simply because the baby is suspected of being big. Which is interesting because both guidelines support induction in the case of GD with high BGLs where the only significant risk factor for birth is a suspected big baby.

Women with high BGLs in pregnancy need to consider the risks of possible shoulder dystocia with the risks of induction (see Berger and Melamed 2014 ) and their own individual situation and preferences. Many women with abnormal BGLs can and do have physiological births, however most follow care provider recommendations and have their labour induced. The following are some suggestions for reducing/managing complications associated with birth for women who had high BGLs in pregnancy. Most of these suggestions can be applied to physiological labour or induced labour – although an induced labour is likely to result in a smaller baby.

- Maximise the size of the pelvis – avoid positions that restrict the movement of pelvic bones (eg. don’t sit on the back of the pelvis)

- Maximise the ability of the baby to rotate – A mobile mother offers lots of opportunities for baby to move – water immersion is good for this. Resting space between contractions also allows the baby to move when the uterus is relaxed. If syntocinon is regulating contractions, make sure there is a good ‘resting space’ between the contractions (no more than 4 contractions in 10 mins). If the woman has an epidural her care providers / support people will need to assist her to move her pelvis (eg. pelvic rocking using the drawsheet or towel).

- BG management – if the woman is insulin dependent it may be necessary to check BGLs during labour.

- Avoid interventions that cause wounds eg. c-section or episiotomy. High BGLs can interfere with healing and increase the chance of infections.

- Avoid any interventions that interfere with instinctive behaviour as the woman pushes her baby out. If she has an epidural then avoid directed pushing until the baby’s head is on the perineum – and then keep it gentle with spaces in between for re-oxygenation of mother/baby and a chance for baby to rotate and move. Do not pull on the baby’s head immediately after it has birthed – this can wedge the shoulders into the pelvis before they have had a chance to rotate. If there is no change with the next contraction (no rotation or descent) – then suspect shoulder dystocia. and manage accordingly.

- After birth do not remove the baby from their mother – this will result in a stress response that will burn up the baby’s glycogen (glucose stores). These stores will be needed as the baby re-balances their metabolism. Any resuscitation should be done with mother and baby together.

- Prolonged skin-to-skin with mother will stabilise the baby’s heart rate and temperature; reduce stress; and encourage early breastfeeding – all great for maintaining BGLs.

- Ensure the baby feeds early and often. Colostrum provides a nutrient dense package of glucose to help the baby keep their BGLs within a normal range. Even a few drops can increase the baby’s BGLs significantly. Woman can express and store colostrum at the end of pregnancy to provide additional colostrum for the first hours after birth.

- The baby may have their BGLs monitored as they adjust to the withdrawal of high maternal BGLs. Any monitoring and/or management can be done with mother and baby together. Separating mother and baby is detrimental for all kinds of reasons, including BGL stabilisation.

- Observe the baby during the first week for jaundice. As discussed above, significant jaundice is fairly common for babies who produced high insulin during pregnancy. The baby may need light therapy to resolve their jaundice.

Summary

High BGLs in pregnancy alter the growth and development of the baby, increasing the chance of particular complications occurring. However, the label ‘gestational diabetes’ is problematic because it is poorly defined and there is a lack of evidence to demonstrate that labelling and treatment improves outcomes. Guidelines do not support induction of labour for GD unless BGLs are high. Inducing women before 40 weeks with high BGLs reduces the chance of a large baby and shoulder dystocia, but increases the chance of other complications. Labour and birth care for women with high BGLs should centre on minimising the chance of shoulder dystocia, and supporting the baby to regulate their own BGLs after birth.

Thank you So needed.

Also – the damage incurred to baby forever after – whilst this ridiculous ‘test’ is done. (Plus the panic mum goes into)

(And if not careful follows the ‘eat more bread’ advice?

Warm wishes Heather

*Best wishes,*

*Heather Bruce *

Transformative Energy Body Worker Founder of Heather’s Gentling Way

Accredited Mercier therapist Arvigo® /Maya Self Care teacher, Certificated and Pregnancy Arvigo® worker

http://www.heatherbrucehealing.com

10 Kitchener St, Coorparoo, 4151, (Brisbane) AU

(07) 3899 2274

Another fantastic, clearly written resource. Thank you!

Thanks for the awesome review and proof-reading x

I always appreciate your posts and devoured them when I was pregnant. I didn’t have GD but I did have an 11 lb baby at home in the water with no tearing 😉 My claim to fame. I have seen some friends be induced for GD citing the reason of a big baby and can’t help but contrast my experience.

Blessings to you ✨

Sent from my iPhone

Thanks 🙂 11 lbs is very big! I might write a post on ‘big babies’

My boy was 5.5kg/12lbs, vaginally delivered, no intervention, no pain relief by choice and all well. Luckily for me the hospital underestimated his size during pregnancy at a mere 10lbs other wise we might have had a different experience.

Interesting read. I landed myself a GD label in the public system because my 1 hour result was 0.1 over the limit. Was well within normal by 2 hours. This lead to much stress, instant dismissal from a birth center and insistence that if I don’t go through the obstetric team and dietary team I’d end up with a dead baby (don’t you love how obstetricians are so supportive?!). Long story short, found a wonderful independent midwife and had a wonderful homebirth with a 3.4kg bub.

I’m pleased you found your way out of that one! The 1 hour result is not recommended for diagnosis. Great evidence-based practice there :/

Can you please explain why is the 1 hour result not recommended for diagnosis? I am currently going through self-testing and my doctor has told me to check only after 1 hour so I would love to get some insight on this please. Thank you.

As mentioned in the post the GCT is no longer recommended because it lacks sensitivity and specificity. It is not very accurate. It is still used in the US.

The 1 hr OGTT is a screening tool (and IS used that way in the US) – if she fails the one hour a diagnostic 3 hour is recommended. We do not diagnose with a 1 hr.

Thank you for writing this helpful and informative post which I will definitely be using as an information source with my clients. During birth care, I presume you are taking as read optimal cord clamping (“waiting for white”) as a given as this would assist the baby’s perfusion and assist in the break down and excretion of bilirubin. Brilliant piece and will be sharing. Please keep writing!

Yes of course… I’d assume that was standard in any birth 😉

Thankyou for this very informative and well explained, evidence based article.

I have recently supported a woman who was being induced at 35+4 and who had normal blood glucose during the beginning of her induction. I do not yet know the outcome of her induction. But it is so important that women have this information so that they can make their own decision. Sadly this isnt the case at present. Language of care givers can be very coercive.

I was dx with GD during my 2nd pregnancy. I had taken my 3hr glucose test and was told I failed 1/4 draws but passed. Switched providers to vbac. That ob said I failed. I tested my bs 4x a day with perfect results. Almost a month in, their own diabetes specialist asked why in the world I was testing as my numbers were normal. She spoke with my ob, who then had a nurse call to say my numbers were out of control & stuck me on meds. Said meds dropped my baby dangerously low and I nearly crashed. When I reached my destination( after quickly eating a candy bar to bring up my sugar) tested my bs at 50! The ob refused to take the diagnosis off my chart. That birth ended in a bullied section after being induced for a ” big baby” who was ONLY 8 10. I took and passed the GD test with #3 & was still labeled GD baby was 8 12 and my first vba2c. I refused the test with #4 and tested my bs with normal numbers which I shared with my provider and she was 10#5 oz. Again, my chart said I had GD. Not one of my babies had any issues often associated with GD. With #2 they CLAIM he had bs issues but REFUSED to tell me his numbers, just threatened to put him in the NICU. If I get phone again, im testing at home again. It doesn’t matter if I think and pass their test, they’ll label me whatever they want.

Thanks, as always, for such an informative piece! I had been keeping my sugar intake low for years before getting pregnant, so I cordially refused the glucose test because I was worried about getting a false positive (everyone is expected to take it in Spain, and I was already sceptical as I was under 35 and with a BMI of 19). Instead, I kept a chart of my blood sugar levels before and after meals for a full week; the gynaecologist at my next appointment cordially refused to look at my chart. She also reminded me that I would be in the high-risk unit no matter what since my pregnancy was achieved through IVF.

Some time after that, I changed hospitals. I was pleased with the change overall, but found that too many midwives were obsessed with the notion that you could not gain more than 9 kg in pregnancy. I don’t know what evidence they based this on, but I measure 1.74m and it just sounded ridiculous. Amid much head-shaking and big baby shaming, I gained 12 kg.

My big baby, born without interventions at 39+4, weighed 2.6 kg.

I myself unfortunately got labelled with GD after 20 long weeks of extreme morning sickness. I was considered boarderline GD and throughout my whole pregnancy it was managed diet only. I think I only ever got two high readings.

Unfortunately during that time I became very distressed from the effects of the morning sickness and the bright red DIABETIC sticker on the front of my pregnancy notes just pushed me over the edge into madness which saw me at my lowest point and in complete guilt panic testing my bloods on the hour and I stopped eating altogether which ended up in me being admitted for a drip.

They kept telling me my baby was measuring large at scans and told me that I’d be looking at my baby being over 11lbs. I even had a private scan done also and they told me the same. By this point I was even more distressed than before.

Anyways long story short, was induced early at 37 weeks due gallstone problem in which the gallbladder was removed two weeks after the birth. My birth also ended in an emergency c-section and my prophecied 11lb baby ended up being a healthy 7lb baby boy who is now 9 months and thriving.

More research and support needs to be done into GD to ensure Mothers are receiving the right care to meet the individual needs of their pregnancies rather than being shuffled into unecessary practices.

To all other GD mothers, look after yourselves and do what is best for yourself and your baby.

Thanks!! I feel Your pain. Glad everything at the end was good x

Thank you for your hard work!!!! WOoohooo!

I have seen so many birth clients (Independent Birth Education) “diagnosed” with GD.. and they are then recommended and feel pressured/scared into monitoring their levels three-four times a day – by bloods ! Which of course is the last thing a pregnant woman wants to do everyday. These clients often NEVER get another reading OUTSIDE of normal and yet STILL get treated as high risk and pressured into ongoing extra tests, inductions and many other interventions.

I will look forward to knowing I now have an accurate, recent and well written article to assist them to understand the circumstances and choices around their health management and risks.

And maternal cortisol (stress) is know to be detrimental for growing babies… so lets stress out pregnant women :/

I am not a midwife, yet as the sperm donor 😉 I did continuously prepare myself to be fully involved in my pending child’s birth; further, I continue to keep up-to-date w/ literature on some of the topics b/c I enjoy helping other newly pregnant partners succeed w/ birthing a healthy baby and momma in USA-context of big box hospital/birthing-center culture. Thus, I will plop a comment here as though I too were a midwife (further, I will share my comment with our hired midwife, who coached us during the birthing of our super-cute baby, 23 months old at this writing).

Given my partner’s comprehensive $15kUSD/yr insurance coverage (USA), she decided to meet with Ob teams (three over the course of 41 weeks). We each having lived for 45 yrs on this glorious planet meant she was labeled “high-risk” and treated as a diseased and handicapped individual, even as her biomarkers came back excellent throughout the 41 weeks, including fasting BGL of 3.6 – 3.9 mM & normal peak post-prandial responses coming down to 5.5 mM within 90 minutes. Note: We did not bother w/ any of the institutional OGTTs; rather, once every two weeks, we both (using the same $25 glucose meter & $2/strips, w/ I as sole control subject) constructed multiple-hour capillary glucose curves using the ancient practice of … drum role please … eating our normal meals!

While we were careful to not mindlessly compare the epidemiological OGTT data to our glucose responses to delicious & nutritious meals, I think we collected contextually relevant data that could be reasonably “acted upon” if comparisons to epidemiological averages suggested a need to intervene. I think this could be correctly referred to as an “evidence-based approach”.

Last, I think any “normal” healthy (or even completely naive) pregnant person should be offered the opportunity to be coached/instructed on how to measure capillary glucose, and any partners involved too. I think of it as part of the process of self-awareness, even self-ownership. Sovereignty.

Congratulations on your super-cute baby! 🙂

Self-responsibility and Sovereignty should be fundamental to midwifery practice: https://midwifethinking.com/2016/06/28/responsibilities-in-the-mother-midwife-relationship/

“BGLs are only high in early pregnancy in poorly controlled, pre-existing diabetes”

I have to disagree with this, as so many other GDM mums. My blood sugars were perfectly fine between pregnancies, and now at 14 weeks I’m already getting high readings.

That’s interesting – pregnancy hormones are not usually high enough to cause insulin resistance until 20 weeks. Have you had an HbA1c test?

The statement relates to current medical knowledge and clinical guidelines rather than my opinion.

Yup. I’ve also asked in the GD UK group and it’s plenty of us!

That is something that needs to be looked at then. If women have high BGL in early pregnancy it can effect the development of the baby during that critical stage ie. as the organs form. That increases the risks of congenital abnormalities.

It seems like it is looked at, depending on where you are. In my trust they recommend you start testing at 14 weeks.

Do you have a reference for the 20 week definition?

Yes they do test earlier if you have previously had GDM or have risk factors.

The reference is from the text book Medical disorders in pregnancy: a manual for midwives. However, the 20 weeks is also stated in guidelines etc. If you can find me a different source stating something different I will change the statement. However, for most women due to the physiology/hormones they are unlikely to get insulin resistance before 20 weeks… unless they are already insulin resistant.

When I say ‘looked at’ I mean scientists needs to re-examine the understandings of physiology/pathophysiology (that are stated in books and guidelines) if lots of women experience high BGL before 20 weeks. The current recommendations re. timing of testing are based on this understanding of BGL rising after 20 weeks.

Thank you for posting this. I think this article is fantastic but I also disagree with this statement. I’ve had a HBA1C and tests after my previous GD baby. I am not prediabetic. There are many many women ont the GDUK group in the same boat and personally I feel there needs to be a lot more research done into why we develop GD early and what that actually means for our babies because currently we seem to fall into the category of lumped with Type 2 or fobbed off. It’s a failing by world health professionals and bodies. So personally I would say the current medical knowledge and clinical guidelines are failing women with early diagnosis GDM.

Many thanks for this informative article. It’s very engouraging for me. I have been diagnosed with gestational diabetes at week 28 (and very grateful for this, as I didn’t feel well after eating fruits) after a GGT (due to my age, over 40 – apparently 12 % of women over 40 have GDM). BGLs are stable now and I hope to avoid induction at week 39, but it won’t be easy.

One thing – you write “Long story short – the usual GD recommendations involve a high carb (ie. sugar) diet.” Is this correct? I was adviced to have a high-protein based diet. As this was already the case, I had lowered my carb intake even more so that eventually I was advised have more carbs (while at the same time I took a bit more insulin).

You never address #3, women with normal BGLs

Women with normal BGL do not have any addition risks regardless of whether they have the label GDM. This is the whole point of the blog post. Normal BGL = no need for the baby to increase insulin production.

Fantastic article, makes sense all round, keep up the good work Rachel.

As always I enjoy reading your posts. I have been researching the thresholds for diagnosis of GDM that are now stock standard in our maternity care. I notice in your comments above that you say that the one hour result should not be used in diagnosis. WHO and multiple others are including the one hour in their diagnostic criteria. Is there some references you can point me to that support excluding the one hour result?

The 1 hour result should not be used alone. WHO note that there are ‘no established criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes based on the 1-hour post-load value’ (p. 5) http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85975/WHO_NMH_MND_13.2_eng.pdf;jsessionid=1A0B9E335D1E4DFA5788471383748B72?sequence=1

The 2 hour reading holds more weight in terms of diagnosis 🙂

Thank you for the article!! It is so frustrating to have this label. I feel like I’m wearing the Scarlet Letter 🙁 I am looking on your blog for information about NSTs… I know they are not evidence based to be necessary in women who are diet controlled, but yet some practices still choose to do them once, or even twice per week starting at 32 weeks! I am GD, diet controlled so far at 28.5 weeks and would like to do as LITTLE intervention as possible (no NSTs or additional ultrasounds before 40 weeks, no induction, no meds, etc.) provided I can remain without further risk factors. Do you have anything you can share about NSTs? I have found research on the risks for ultrasounds. Thank you!!

There is no evidence to support routine NSTs for women with normal BGLs (regardless of their label). The intervention is done ‘just in case’ and because despite all the evidence there is a belief that u/s can accurately estimate the size of a baby. It is up to you whether you want to accept the offer or NSTs. And you do not have to provide your care provider with a reason for declining their recommendations. However, they have to provide you with good evidence and information about any intervention they recommend.

Hi Rachel,

Are you aware of the recent case-control study which seems to suggest that there is a greater risk of term stillbirth for women with risk factors for GD who are not screened, compared with no additional risk for those that are?

And also that women with raised BGLs have a 4-fold increased risk of term stillbirth, compared with those screened and treated as GD? This study seems to demonstrate that women do in fact very much benefit from being “labelled” as GDM and treated accordingly.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1471-0528.15659

Thanks for sharing this – I can’t access the full article. Can you quantify 4-fold into something meaningful for readers ie. from x.x% to x.x%… I am guessing we are still talking extremely small numbers. Women need to have this information to make an informed decision about whether they want routine screening or not. Also what other outcome measures/risks were looked at? Again necessary information for individual decision making.

Screening or not (getting a label) is up to individual women… and they need adequate information rather than fear/risk based information such as ‘4-fold’ – NICE provide some good guidance for care providers about presenting statistics in an objective rather than fear-mongering way. Women also need to consider the risks that come with the label (as discussed in the post) – not just one small risk (stillbirth according to this study).

Thanks for quick reply Rachel! I do appreciate the need for clear and not fear-mongering stats, but unfortunately the world of medical studies doesn’t always (often!) work in this way (as I’m sure you know, not trying to patronise you!). We rarely get huge, well-powered RCTs because thankfully our worst outcomes are indeed uncommon. We have a patchwork of studies suggesting relative risks, and even big population studies may not have been done in the UK. When big population studies are done, people often complain that they can’t be trusted because the populations aren’t directly comparable to the UK, or important details got lost in the compound measures!

As a case-control, this study can’t comment on incidence/prevalence – the cases were all chosen specifically because they suffered a stillbirth, the controls didn’t, this wasn’t a sampled population. So we can’t derive an “x to y%” risk increase.

They excluded controls with congenital abnormalities or multiples, but that’s a relatively low proportion of stillbirths. Also, whilst the study says “late stillbirths”, their inclusion criteria was >\=28 weeks; that seems more like all stillbirths to me (or at least most – perhaps trying to distinguish between miscarriage for a lay reader).

So, crude calculation… knowing that the rate in the UK is approx. 4 in 1000, and let’s say 1 in 1000 is either 24-27+6 weeks or congenital abnormality (which is probably a gross overestimate), that’s going from 0.4% risk to a 1.6% risk (again, more likely an underestimate).

According to RCOG guidance on describing risk, that takes it from “uncommon” to “common” (although I would never describe it in those terms), but still, I really don’t think that difference is to be sniffed at. Given that a busy GDM clinic might see over 30 women, that would be equivalent to 1 woman in every 2 clinics experiencing stillbirth if they didn’t receive screening/treatment, compared to 1 woman in every 8 clinics with treatment.

Thanks Tom. That helps to put it into perspective. Research is very problematic in maternity care – I wrote about that here: https://midwifethinking.com/2017/01/23/research-bias-and-maternity-care/

Perhaps the label of GDM would not be such an issue if it didn’t then result in a pathway that includes over intervention – in particular early IOL. The risks of those interventions also need to be considered eg. increased c-section rates = increased subsequent stillbirth rate etc.

BGLs are clearly an issue and perhaps all women should be supported to have optimal nutrition in pregnancy ie. evidence based nutritional information. Our maternity systems are set up to identify and treat rather than promote wellness and prevent complications.

I will see if I can get access to the article via my uni and include it in the post.

Interesting that nowhere you mention stillbirth which is what we are threatened with if we don’t agree to induction. Was there anything to suggest this in the research?

Increased rates of stillbirth used to be associated with pre-existing diabetes rather than GD. So older studies that just looked at ‘diabetes’ (combined groups) would have higher rates (still very low).

However, the latest research distinguishes between the two types of diabetes and the risk of stillbirth for GD is not higher. It is also not higher for pre-existing diabetes in recent studies… because we are better at planning and supporting pregnancies in that group of women. I discuss this and the research in my boom 😉

Sounds like who ever is threatening is out of date re. evidence based recommendations.

Happy to read this – reassurance that I’m not crazy. Based on my experiences, I knew I would want a homebirth and so here I am, trying to fit into a small square of expectations and criteria for homebirth within private (group practice) midwifery care and still being told that if I don’t do the GTT, I may be denied a homebirth. My only risk factor is that it’s my first baby.

Student midwives spend so so much time learning how to advocate for women, how to empower women, how to help women make informed choices and yet, as a pregnant woman, that is not the care I have received.

No wonder women freebirth. The whole thing has caused me so much anxiety.

Hi I just hit upon this very informative post, and I am wondering if a woman has proper gd during her pregnancy, what does that mean for future pregnancies?

She is more likely to have the same diagnosis with future pregnancies because this is how her body responds to pregnancy.

She is also more likely to develop Type 2 diabetes later in life.

I noticed one comment about many women being diagnosed with GD before 20 weeks who did not have pre-existing Type II. I know a woman in this situation and it was due to the difference in the fasting definition of >6 non-pregnant and >5 once pregnant. Her fasting level was in the 5s and non-fasting was within the parameters, so the instant she became pregnant she was “diabetic”. I wonder how many of the women diagnosed early are in this category.

Thanks for all your hard work Rachel. It is invaluable.

Thankyou for your well researched and explained article.

I am currently in Australia and deciding if I will have this test.

I tried to follow along but I did not see the “old” BGL levels for pregnant women verses the new BGL levels for pregnant woman.

I will do the test because I am older and overweight, how ever I want to know where I sit with the old levels as well as the new levels (since there doesn’t seem to be strong support for using the new levels)

I am under private midwife care, so am confident I won’t be issued the dead baby card, however if I do end up with diabetes I’d like to work with my naturopath and the rest of my team to manage that.

They lowered it from the standard non-pregnant levels (in the post) ie. decided the parameters were lower in pregnancy.

Hi! I was wondering what would be classed as high BGLs during pregnancy. If a women is mostly controlling her BGLs under target but goes over a few times a week is she still classed as controlling them or not?

High BGLs are defined differently depending on who or what (organisation). For example, pregnancy thresholds are often different to non-pregnant thresholds. Same with the definition of ‘controlling’ levels. Each women needs to consider her own situation and decide what is best for her. Numbers and thresholds are generalised rather than individual.

I’ve learned more in this blog post than my first 23 weeks of pregnancy and antenatal care with pre-existing diabetes (type 1, 17+ years). I know it focuses on GD but it’s been invaluable to my understanding as a type 1 diabetic too. I’m so glad I found this (I was sign posted to it) and wish this had been explained to me at the beginning of my pregnancy. THANK YOU.

Hi, as a student midwife and someone who is currently 16 weeks pregnant I found this post extremely informative!

All of the current research evidence leaves me wondering how I can make an appropriate decision about screening. I am leaning towards declining the OGTT as even though I don’t have any risk factors, I am nervous about this low threshold leading to a diagnosis that is not evidence based/related to outcomes and could result in prohibiting a water/home birth (as I am going through caseload hospital care that does have a homebirth option). On the other hand, I do want to avoid the negative outcomes associated with true high BGLs if I were to have undiagnosed and uncontrolled GD. Do women in this position often opt for self-testing to gauge risk, even though it is not recommended? Or is there a magical third option?!

Obviously your post clearly indicates the need for an assessment/thresholds that accurately does what I am looking for… it will be something I discuss with my midwife, but I would love to know in your experience any other kinds of avenues women opt for when they don’t want to go through the standard OGTT thresholds.

Thanks so much for your clear summary of research in this post!

Individual women approach their pregnancy and birth differently. I’ve seen a wide range of approaches. Many just don’t engage with the testing and focus on health and wellbeing. 🙂

Sorry so late, hope you’re very very well 💖

We pricked fingers together for a month, during fasting, throughout meals, and pre- and post-exercise. Presented the data to our OB and thankfully she didn’t roll her eyes. But she didn’t care, still asking to schedule an OGTT. Nahhhh, we’ll RISK it 😉

(Outcome was excellent, natural birth during week 41, in spite of old egg & sperm).

All going well?

Best regards from Arizona, USA!

Many thanks for this nice and informative article, it really corroborates all my intuitions during this GD process. I am 34 weeks pregnant and diagnosed with GD since week 26. My levels during the day were, and still are, normal (between 5 and 7 mmol/L after 2h) but the fasting levels were some decimals higher (between 5.4 and 5.8). I practice sport and eat healthy so they decided that I need to take slow insuline because it seemed that the placenta was the cause of the DG. I started with 6 unities of Insulatard and now i am at 30 unities and still the fasting levels are always between 5.2 and 5.8. The rest of the day has always been fine. I also got a continuous glucose reader Freestyle (in spite of my doctor’s recommendation who claimed that a continuous reader will not be helpful at all! Crazy ideas, it was the best decision I could have made!) and my levels are quite stable during the night, with no funny peaks.

I was told by my obgyn that i will be induced at 39 weeks per protocol and he was not very pleased when i told him that it is a procedure i will only accept in case of imminent danger for baby, myself or if the placenta is no longer a safe house for my daughter. Without doing any individual risk assesment nor even being interested in my glucose levels, he started threatening with the risk factors and possible negative outcomes and when I asked about the prevalence of all these negative outcomes, he could not answer but to say that is still rare phenomena… i also asked about the specific risk in my individual case and he obviously could not answer me.

I am worried and I feel lost about what is the right decision because I know that I am not part of the group of fully controlled diet-exercise GD but also I have no uncontrolled levels, I gained only 6 kgs so far and I still have active lifestyle, practising sport and feeling great. I of course worry about being too stubborn and putting in risk my baby but I really want to avoid an induction for just “prevention” when we know that its risks are not negligible.

Ideas, advice or experiences are welcome, many thanks for reading!

If it were helpful, I wish I were reading this earlier to give two cents of support! 💖

We opted-out of the sugar drinking screening and instead used several weeks of finger-pricked data (Soooo jealous that you had a CGM!) during fasting, over the course of meals, and post-exercise. Fasting came down from 5.5 to 4.2 mmol/L due to pregnancy, so we lost any glucose management concern. Understood that you had some concerns since your pregnancy-levels were at “normal, high” levels for non-pregnant women — did you have previous knowledge of your pre-pregnancy glucose levels?

Anyways, curious how it all went for you!

We too had zero institutional support, and simply did not show up from week 39, on, for the induction & drama. Natural birth progressed & w/o intervention during week 41, and that our fully healthy, 4′ 2″ tall daughter is approaching 6 yrs, we have no regrets of a low-anxiety home-birth (1st child, yikes!). It cost an extra $3500 since no support for midwives working as a second-opinion in Arizona, USA… cha ching.

(Week 39 induction “requirement” was due to risks correlated to age: 45 yr old sperm, 45 yr old egg!)

I was diagnosed with GD at 28 weeks (currently 38 weeks) and have been diet/exercise controlled the whole time. Growth scans have shown my baby to be healthy and normal. At my appointment last week the midwife said that I would need to be induced between 40-41 weeks due to the risk of placental failure. When I questioned her on this she said that GD makes the placenta break down more quickly regardless of whether I was medicated or not, and that if I were on insulin I would be induced at 38 weeks, and if I did not have GD I would be induced at 42 weeks. I have not been able to find any information about this online. Are there any resources that I can look at to confirm this? (I would rather not be induced if I can help it.)

There is no evidence for that statement. If a care provider is recommending an intervention it is THEIR responsibility to provide you with evidence to support their recommendation. Not your responsibility to find evidence to support you declining their recommendation. Ask your midwife to provide evidence. She must do this to meet the requirements of consent.

If it would have been helpful, I would have liked to reply w/ supportive statements. The scary if –> then statements regarding Inducing birth were premature by the midwife because this outlook merely “induces” fearful thoughts, potentially long-lasting anxiety.

How are you now? And baby?

If you have the chance, would you summarize your birthing experience for us?

Thanks again for a fabulous article, and updates. I’m a midwife, and get judgemental looks from colleagues when I dare to suggest that women with normal BGLs despite a GDM diagnosis, are at no more risk than anyone else. That being said, I recently had a baby whose mother was in that category, and developed hypoglycaemia requiring intervention. It was a reminder to me that vigilance is still required. Sadly the hospital where this occurred has very high CS rates, and the woman had had a CS at 38+5 (because of all the usual scare talk) so this may account for the hypo.

I recently was asked by a friend’s sister for some guidance around her booked IOL at 39 weeks. She is a multipara, no other issues, well controlled BGLs (albeit with insulin nocte), fit. I sent her to your blog, and to Sara Wickham’s, and suggested she look at the NICE guidelines which recommend IOL before 41 completed weeks. I reminded her that she could ignore the recommendations, and ask for closer monitoring instead. She had been told that her baby was big and her placenta was at high risk of dying (I don’t have enough eye rolls for this), so I said that only a doppler could indicate any reduced blood flow. She did look into it, and was grudgingly ‘allowed’ more monitoring instead. Surprise, surprise, at the very first CTG (I hate those things) it showed he placenta WAS dying, and they said she needed to go ahead with the IOL straight away. And no prizes for guessing the outcome. From planned second SVB, to CS. And the baby was 3.6kg. I’ll add that to my ‘cautionary tales’ files.

Thanks for your informative blog post follow up and the podcast episode. I found it really eye opening and so refreshing to hear an honest take on the whole GD testing shenanigans and diagnosis criteria. I am 32 weeks with baby no 3, and declined the GTT with my second baby, and fasting bloods were fine for him. I declined it again and opted to do the fasting blood only this time round and was told I am “borderline” at 4.7. They are recommending doing the full glucose challenge and are offering me a growth scan at 36 weeks because my son was big for his gestation (my little boy was born at 38 + 3 – natural onset labour and was 4.11 kgs- hubby is also 6 ft 2 1/2 so that could also have impacted his weight). I think after your podcast episode and this blog I’ll decline both but I wanted to know about what limits I would look for if doing home self testing? I don’t even know where to start! Thanks so much!

First, the borderlines are the upper and lower bounds from measurements from a population of people like you (female, age group, etc.), and since your 4.7 mM falls within that of the Normal population, the correct disclosure to you from your healthcare provider is: “Your fasting glucose level is Normal”. Second, the OGTT is a neat challenge to your body when offered under controlled conditions. Since my wife & I *a)* are not lab rats and *b)* prefer not to ingest processed foods, we set up our own OGTT several times over the course of pregnancy. (We had also done so before pregnancy.) You would need to buy a reputable finger-prink blood glucose testing kit w/ enough strips to take several measurements before- and after- “challenging” your body with the food. You would also need to carefully read the instructions in order to retrieve the best blood sample possible with each poke. We chose normal meals, going out to eat meals, as well as meals with bigger desserts, and finally, the often-maligned pizza & salad meal. I recommend doing so pre- and post-exercise too (she used to “speed-walk/jog” to work, up until the day before birth).

If anyone reading this blog, including @MidwifeThinking or @beth has any expertise/understanding of the placenta, I am curious to read more about the idea of placental “death”, “life cycle”, etc., as I had not heard that one before. Presumably the blood flow rate is measured regularly in order to identify changes? (It makes sense that each sonographer would estimate blood flow, technology/experience permitting). Thanks for considering.

Superb article and I’ve also listened to the two podcasts you did. Really eye opening and helpful for me at 39+4 with a GD diagnosis. I am getting so much pressure to induce or break my waters, which I have so far declined. But they keep saying that the placenta of women with GD stop working well after 40 weeks even when they have normal BGS levels managed by diet and exercise, and the research shows this (though they can’t direct me or quite which research). I’d love to know what your thoughts are on placenta function of pass 40 weeks? Many thanks in advance!!

I write about placenta in my book Why Induction Matters and in this post https://midwifethinking.com/2016/07/13/induction-of-labour-balancing-risks/

If your carer providers are recommending an intervention, it is up to them to provide you with the evidence to support the intervention (by law).

This is really interesting, I supposedly have GD but my numbers when testing have all been fine and that with no changes to diet. Do you know why they came up with the threshold they did? If I go off the type 2 threshold I’m no where near that even so I’m struggling to see why I should accept any care when my body is seemingly dealing with what appears to be natural insulin resistance well? Great blog post

They based the threshold on the probability of a large baby. Not on poor outcomes.

Fascinating article.

When I went in for my test, I happened to have read up about it a few days previously and discovered that the conventional test is usually only offered to pregnant women and is potentially dangerous as some women’s blood sugar can drop dramatically. So, I declined the test and only then was I offered the 7 day pin prick test. Unfortunately, I was eating too much fruit at the time (summer) which was unusual for me, so my levels spiked 4 times, which gave them the excuse of declaring me as having GD.

Ever since going back to my normal diet of meat and veg, my levels have stabilised, though I have found, very interestingly, that readings can differ according to which hand I use and sometimes even which finger. So those monitors are unreliable.

On a separate topic, have you done any research into placenta praevia? I am due to go in for a C-section within a few days because mine is still covering the cervix (supposedly). I am not happy about this, but I have managed to convince the doctor to postpone it to 38 weeks rather than the conventional 36-37. She, on the other hand, produced a document (how reliable I don’t know) stating that to push it back to 39 weeks increases the risk of bleeding to over 50%. How true is this?

Thank you for the great article Rachel. I was ‘diagnosed’ with GDM at 37 weeks with my last baby, although during pregnancy I had passed the GDM test. This was due to a late growth ultrasound scan which showed the baby was ‘macrosomic’. They ended up inducing me which led to emergency c section. Baby came out 3.7kg and very healthy. With my second pregnancy (currently 35 weeks) blood sugar has been normal (I test myself at home) but at a scan yesterday they said my baby is on 95th percentile and her stomach is measuring big (indicating GD). I know scans can be quite inaccurate, but just wondered what your experience/opinion is on diagnosing GD from ultrasound scans?

You can’t diagnose GD via an ultrasound. Normal BGL will not cause the baby to increase insulin production and become macrocosmic. Growth scans are inaccurate. See my biog post on big babies for more information on that.

I have just come across this article I was diagnosed at 33weeks with gestational diabetes my fasting level was fine but after it was 8.8. My baby was growing fine on the 54th centile since I have reduced carbs and cut sugar my baby has now dropped to 8th centile. I am worried that perhaps it’s due to my significant diet change could this be a possibility?

Ultrasound cannot accurately estimate the size of a baby.

Hi Leanna, my response is first, to agree with Ms Reed that the growth percentiles are not your big concern, especially at this stage. Second, are you indicating that your week 33 fasting level is 8.8? Or after ingesting a pure glucose solution, it measured at 8.8 at X hours post-ingestion?

It seems reasonable to cut simple sugars, but “reducing carbs” would only make sense to me if you were previously on a purposefully high-carb diet; otherwise, please consider going back to a fairly average diet of 50-65% carbs, but make them nutrient-dense choices (including fiber of course!).

Last, what exactly did your pregnancy team suggest/recommend following your glucose measurements?

Best,

Jack