Updated: August 2019

This post has been inspired by conversations I’ve had with women about their experiences of induction. Induction of labour is increasingly common, yet women often seem to be very mis-informed about what it involves, or what was done to them during induction and why. For example, one woman was told by her obstetrician that induction would involve him using a pessary to ‘gently nudge her into labour.’ Women need to be given adequate information in order to make birth choices; and practitioners need to give adequate information in order to meet legal requirements. I have written about the risks of induction in a previous post so will not repeat myself here. Instead, this post aims to provide some basic information about the process of induction – what is done and why. I would really appreciate input from readers about their experiences of induction – what was done, how it felt etc. I am hoping this post will be a resource for women who are considering induction, or are unsure about what happened during their induction.

In my old 1997 version of the ‘Midwives’ Dictionary’ induction is ‘causing [labour] to occur’ ie. someone causes a labour to occur rather than allowing the baby/body to initiate labour. The dictionary goes on to say ‘this may be carried out when the life or health of the mother or fetus is in danger if the pregnancy continues.’ Of course this statement is open to interpretation and most inductions are carried out because of a variation to pregnancy (eg. postdates) rather than a complication (eg. pre-eclampsia). Regardless of the reason for induction, the process is fairly standard.

Making the decision

The decision to undergo an induction of labour is the woman’s – you can read more about roles and responsibilities in the mother-midwife (or other care provider) relationship in this post.

The National Institute of Health Care Excellence (UK) provide guidance for health professionals about what information they should share with women when offering induction:

- The reasons for induction being offered

- Where, when and how induction could be carried out

- The arrangements for support and pain relief (recognising that women are likely to find induced labour more painful than spontaneous labour)

- The alternative options if the woman chooses not to have induction of labour

- The risks and bene fits of induction of labour in specific circumstances and the risks and bene fits of the proposed induction methods

- That induction may not be successful and what the woman’s options would be.

There are a few things you need to be clear about before choosing to be induced:

- That the risks involved continuing the pregnancy are greater than the risks involved in induction (risk is a very personal concept – see a quick word about risk).

- You are committed to getting this baby out. Once you start you cannot back out, and a c-section is recommended for a ‘failed induction’.

- You are not having a physiological birth. You have intervened and this intervention creates risks that require further monitoring and intervention. There is no ‘natural’ induced birth – vaginal birth maybe, empowering perhaps, but not physiological.

The Induction Process

There are 3 steps to the induction process. You may skip some of the steps along the way, but you should be prepared to buy into the whole package when you embark on induction.

In a physiological birth the baby and placenta signal to the mother’s body that baby is mature and ready to be born – this starts the complex cascade of physical changes that results in the labour process.

Note: If your waters have broken naturally the term ‘augmentation‘ rather than induction is used to describe getting labour started. This is because it is assumed that your body has started the labour process itself. You can read more about this situation here.

Step 1: Preparing the Cervix

Some practitioners offer a membrane sweep during pregnancy to avoid a ‘post-dates’ pregnancy. The procedure involves a vaginal examination where the practitioner places a finger into the opening of the cervix and ‘sweeps’ it around the inside of the lower part of the uterus. The aim is to separate the membranes of the amniotic sac from the lower uterus – this releases prostaglandins. A Cochrane Review into membrane sweeping concluded that: “Routine use of sweeping of membranes from 38 weeks of pregnancy onwards does not seem to produce clinically important benefits. When used as a means for induction of labour, the reduction in the use of more formal methods of induction needs to be balanced against women’s discomfort and other adverse effects.”

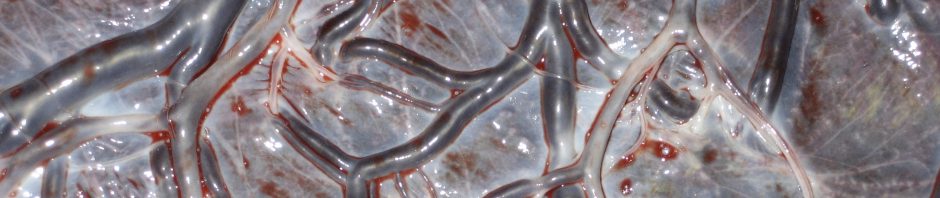

When you are being induced your cervix will be assessed by vaginal examination. If your cervix has already changed and is soft and open enough to get an amnihook in you can skip straight to step 2. If your cervix is still firm and closed, attempts will be made to change it so that step 2 is possible. This is usually done by putting artificial prostaglandins (prostin E2 or cervidil) on the cervix in the form of a gel, pessary or sticky tape. Artificial prostaglandins can cause hyperstimulation of the uterus resulting in fetal distress, therefore your baby’s heart rate will be monitored by a CTG after the prostaglandin is administered. You may also experience ‘prostin pains’ which are sharp strong pains sometimes accompanied by contractions. If there are concerns about giving you prostaglandin (eg. previous c-section) your obstetrician may suggest ways of trying to get your own cervix to release natural prostaglandin by ‘irritating it’ (this is the theory behind membrane sweeps). This is done by inserting a balloon catheter into the cervix and filling it with water ie. you basically have a water balloon sitting in your cervix.

Successfully completing step 1 may take a few attempts with re-insertion of prostaglandins. This can take hours or days because you must wait hours before re-assessment and re-insertion. You may respond to the prostaglandin by going into labour therefore skipping the following steps. However, you are still having an induced labour and will usually be treated as ‘high risk’.

Step 2: Breaking the Waters

Step 3: Making Contractions

- It works on the uterus to regulate contractions

- It works in the brain to contribute to the altered state of consciousness associated with labour and promotes bonding feelings and behaviour

In an induced labour, artificial oxytocin (pitocin/syntocinon) is given via a cannula directly into the blood stream. It is unable to cross the blood brain barrier therefore only works on the uterus to regulate contractions. I have written about the risks associated with artificial oxytocin here along with references. Basically, it can be pretty nasty stuff which is why your baby will be monitored closely using a CTG. Women usually describe artificially stimulated contractions as being different and more painful than natural contractions. Having supported women during inductions I am also convinced there is more pain associated with induced contractions. During an induced labour contraction pattern and intensity increases quickly compared to most natural labours. Women are not able to slowly build up their natural endorphins and oxytocin to reduce their perception of pain. In addition the circumstances and environment that often surrounds induction (intervention, equipment, etc.) can result in anxiety, increasing the perception of pain.

Once your baby is born you will need to continue using artificial oxytocin to birth the placenta. A physiological placental birth is not safe because you are not producing your own natural oxytocin at the level required to contract the uterus strongly and prevent bleeding. Basically medicine has taken over and must finish the job.

In Summary

Inducing labour involves making your body/baby do something it is not yet ready to do. Before agreeing to be induced, be prepared for the entire package ie. all the steps. You may be lucky enough to skip one step, but once you start the induction process you are committed to doing whatever it takes to get the baby out… because by agreeing to induce you are saying that you or your baby are in danger if the pregnancy continues. An induced labour is not a physiological labour and you and your baby will be treated as ‘high risk’ – because you are.

You can read more about induction in my book Why Induction Matters

Hi! In my fifth pregnancy, my blood pressure went up to 145/95 at 11 weeks. It was thought that I would miscarry my baby, but I didn’t. My bp stayed there until 6 months, when it started to rise. At 8 months, when it rose to 190/120, the decision was made to induce. The prostaglandin was inserted at 6:00 Sunday evening. At 6:00 Monday morning, pitocin was started. They continued to increase the amount of pitocin, but labor did not start, and my cervix was closed. They stopped the induction for the night, and started again the next day, with the same result. At that point, they sent me home until the following Sunday, when they repeated the prostaglandin at night, and the pitocin at 5:30 am. At that point, I was at 2 cm, but not in labor. The doctor wanted labor to start before he broke my waters, but at noon, with no contractions, he broke them anyway. I immediately went into very hard, painful labor (and I labor well!). At 5:10, my precious one was born healthy. It was the most painful labor I’ve ever had. During the labor, my bp went up to 245/135!

Thanks for sharing your experience Bonnie. 245/135 is a pretty scary blood pressure :0

No wonder her blood pressure was up with all the stress of forcing her uterus to do what it was not ready to do. Would someone explain to me how all of that extra chemical was supposed to reduce her blood pressure. Was there any attempt to reduce blood pressure with rest medication and counselling during the pregnancy – were you kep in hospital during the antenatal period for observation – those are very high readings>

or may be with 5th child provide home help. I am surprised the baby did not want to get out of there.. What machine was used was it measured with another machine and a different person. Who was measuring the blood pressure? . There is enough prostaglandin in semen to start labour and surely a more pleasant way to bring baby into the world. I am puzzled as to why this level did not harm the baby – something not quite right here.

To birth educator: In answer to your excellent questions: Yes, every attempt was made to reduce my bp with counselling, rest, and meds. Also, child care was organized as my bp continued to rise. I was in hospital on and off, but not as much as usually would be recommended since my husband is an RN, and between him, my mom and a home health nurse, my bp was taken regularly throughout the day. I did have to go in several times a week for various tests. Yes, more than one blood pressure machine and more than one person took my bp. As to why this blood pressure level did not harm baby, I was told first that I would miscarry, then that baby would either die or would have IUGR. They couldn’t figure it out either. I know it was God. There is no other answer.

As to your comment on prostaglandin in semen being adequate to start labor, that sometimes works. Definitely not always, particularly a month early. I am a homebirth midwife now, and I wish it did work all the time!

Bonnie

Well with my sense of humour included ( wry and cynical) it may be depend on whose doing It and if the machine involved was well primed?! I assume your baby was OK? Saturday night on night duty with a full moon and especially lightning and thunder and a relaxed couple would arrive with monotonous regularity and huge numbers (4 years on night duty on Friday and Saturday nights was my experience in a private section of a public hospital). If they were not advanced in labour our message was to send them home with the euphemistic language glass of wine and “nudge nudge wink wink” – in the days before we were able to even say sex?! One couple of doubtful intelligence actually just nudged each other -true story.

To birtheducator: Thanks, my “baby” is 17 now, and gorgeous and talented. She wasn’t entirely unaffected, though. The pediatrician said that she acted as though she were quite premature (reflexes, reaction to light, etc.). Yes, I agree that with a full-term baby, the “nudge-nudge-wink-wink” method often works, but my baby was a full month early, and my body wasn’t about to let her out! Your story about the “nudgers” is hilarious! People! I had two points with my story: one was that sometimes induction is actually medically necessary, and the other is that in my case, pitocin induction didn’t work! I had three days of pitocin induction, which only got me to 2 cm and 50 % effaced. It was breaking my waters that then brought the baby.

Thank you for sharing. I have a client going in for induction of her first child and it is good to hear that a vaginal birth is possible after such an intervention.

Thanks for this Carolyn. I think you’ve written a clear, unambiguous and easily understood explaination of induction – hopefully my own explaination to women & their partners is equally balanced and informative.

You have highligted a very important point: that it is essential for women (and the caregivers who have decided that an induction is warranted) to fully appreciate that the ultimate aim of induction is to birth the baby…that is, if the cervix doesn’t soften or dilate then a caesarian is on the cards. I have seen the induction process abandoned after 2 days of prostin when the woman remains unARMable as noone wants to take the radical decision to perform surgery. We must then ask “was the indication to start induction actually strong enough if it can be abandoned in favour of waiting a few more days? “.

It is also very important that we give women time to fully accept their changing level of risk and the adjustment to care that must take place if we are to be safe guardians of her birth. I think many times, it is a huge challenge for women (and some midwives) who are deeply committed and invested in fully physiological birth to accept that CTG, active 3rd stage and progress/time monitoring (etc) have a legitimate place in circumstances such as an induced birth. That is not to say the birth need be a medicalised circus – we can still create a sacred, calm environment resulting in a positive & transformative experience but we must all respect that the level of risk has changed and our care must be modified accordingly. Getting the balance right is the real challenge we all face.

Finally, I challenge the notion that induction contractions are worse than physiological labour – many women experience intense & overwhelming physiological contractions. I think it is probably the events associated with induction that alter her perception of the contractions and in that way impact on pain perception and coping: continuous surveillance and assessment vs sleeping through or minimising sensations (until the woman herself calls for a midwife/hospital to assess her); concern and stress associated with having a higher level of risk that has led to the induction; the speed of onset and acceleration that can often (but not always) be quicker than a physiological birth – to name just a few.

thanks again for your blog – another wonderful written essay tat gets me thinking

Maxine xx

sorry Rachel, got confused with my bloggers! still think it’s great 🙂

Maxine, I agree with your reply for the most part – this is a fantastic piece Rachel – but I will beg to differ on your challenging of the notion that the induction contractions are not rougher than normal spontaneous labour ones. They are. Only a woman who has experienced both could make this determination with any degree of objectivity, don’t you think? The oxytocin induced contractions do not start softly and build up like the natural ones, and let me tell you they rip through you like a chainsaw in an instant after that drip is commenced. I did not use an epidural during that birth so I feel I can genuinely comment that it was like being assaulted for many hours until the birth of my baby was achieved. For a PPROM at 35 weeks it was warranted, I get that. Compare this with my three other naturally beginning labours that only became unbearable type contractions of the same intensity at the point just preceeding transition, so much less time to cope with that out of control feeling. Anyhow, just wanted to put my thoughts across to balance this point out. BTW, am now a final year Mid student and loathe putting women through the inductions that they beg for!

As a long time practitioner and user of hands eyes and ears when examining women in labour and coming from an era prior to chemicals use I can tell the difference between the strength of labour pains and the perceptions of pain by women and assess correctly. Firstly normal labour starts gently and gradually soft and the musclular tissue is penetratable by gentle pressure. When the graduated contractions of 2nd stage start they feel like a hard brick and last long and strong. When an infusion of artificial synthetic hormone is poured in through a drip those iniitial contractions begin and feel like a brick and do not lessen in strength and are horrible to feel to the touch. There is no gradation. I can only imagine what it feels like – but I recall 2nd stage labour very clearly from my own experience. Epidural is essential in most induced labours – these labours are not fair to the fetus either – because each strong long contraction give pain because oxygen physiologically is absent – just as a heart attack give pain through lack of oxygen. Most babies in the uterus if not being fed properly want to get out. Apart from that there is a great deal of harm caused by the chemicals unknown it seems to most writers – epidural by itself lower blood pressure and requires extra fluid in the system to keep the blood pressure up. All very scary interventions. Of course the artificial breaking of membranes is another story of introducing infection and increasing the pain of labour. The whole story and debacles caused, send my blood pressure up.!!!

From experiencing 3 vaginal births, two of which were induced by gel and later the breaking of waters and one with natural onset, I would have to say that the labour which started naturally and had no interference or monitoring in a very mother directed environment had contractions that hit me all of a sudden with great aggression and no gentle slow pressure build up. Contractions double peaking and one on the top the other and never actually dying down completely. My induced labours were far more calmly progressive and manageable. However, I didn’t need a drip to aid contractions. I really think that the mind plays a huge part in the perception of pain and that women ‘perceive’ that their pain was worse with induction because that is what they read and are told and all the stress that women may feel because they are not having a ‘natural labour’. Maybe the labour was always going to be really painful regardless of how it was started! Once hard active labour started with all 3 of mine the intensity of pain all felt the same between induced and natural onset of labour.

I agree – the perception of pain is influenced by lots of factors. From what you describe you had physiological contractions ie. your own natural oxytocin created them. The ‘drip’ is the synthetic oxytocin and it is this medication that creates contractions women often describe as different and more painful. You had the gel which is prostaglandin hormone to ripen your cervix. You were obviously close to labour anyway and this first step triggered your body to produce natural oxytocin. I am guessing that the labour you describe as starting naturally was not your first baby? Women often find subsequent labours can start more suddenly without the long slow build up of first labours… then again we are all different and so are our labour experiences 🙂

I can only speak for myself, but I was completely ignorant of any difference in contractions or pain between ‘natural’ labour and syntocinon/pitocin induced labour when I had the latter. I was looking forward to labour! Had been for the whole 8.5 months. I really wanted to experience it and was not afraid at all. So for me this ‘perception of pain’ played no part. I had no idea of the differences, ignorant as I was. Now… second time around, having experienced the syntocinon… I am not looking forward to that again and will be bargaining with my Dr on monday to try everything BUT that. I’d love a spontaneous labour, if only to explain my first hand differences in experiences to my daughters in 20-30 years time. But if it doesn’t happen in the next 6 days I will be induced again. I’m ok with this, ultimately. But will surely be avoiding that nasty syntocinon if at all possible!

Thanks Maxine

I agree re. pain is largely about perception. I think increased perception of pain during induction has a lot to do with not getting into the altered state of consciousness via natural oxytocin + endorphin, and with the events associated with induction.

ps. I am quite happy to be mistaken for Carolyn 🙂

Awwwww “blushes” I’m secretly thrilled Maxine thought the post was mine because I love your blog Rachel! <3

Are you making the assessment that induced contractions are the same based on any personal experience or are you just assuming? I don’t think many women who have experienced induced contractions would agree……. An interesting theory that the natural oxytocin isn’t present and therefore women have less natural hormones to help them cope, but I still don’t agree that it is about perception of pain. I think that is why in many hospitals that induction is an indication for an epi

From a physiological perspective a uterine contraction is a uterine contraction and oxytocin whether synthetic or natural acts in the same way ie. oxytocin receptors in the uterine muscle respond to the oxytocin then create a contraction that starts in the fundus and waves down the uterus. Uterine contractions are usually more painful for women despite the fact that the physiology is the same. This is probably due to a number of factors. With a natural labour contractions usually slowly build up allowing the woman to build up endorphins. With induced labours the syntocinon is cranked up every half hour until regular strong contractions happen – often only taking a hour or two. Induced contractions can be too strong and getting the balance between contractions that work and contractions that are too strong is difficult – so often women are experiencing contraction strengths that they would not naturally create. So, it is the context of the contraction pain that makes it more painful because the physiology is the same. Epidurals are often ordered along with an induction because it is known that women experience more pain. Personally I think any woman who gets through an induction without an epidural deserves a medal – I wouldn’t do it.

I agree with what you are saying Rachel, a contraction is a contraction. I also agree that they are pumped up to make them very strong very quickly and therefore many women don’t cope with that in such a short space of time. I don’t necessarily agree with Maxine’s assumption that it is about perception of pain. I do agree that some things help us cope better and worse that are about the mind, but I think the overwhelming anecdotal evidence from women who have had inductions who have found them unbearable in comparison to their un-augmented labours can’t be ignored

I need a medal then…..x….

Ditto! 18hrs…

“Personally I think any woman who gets through an induction without an epidural deserves a medal – I wouldn’t do it.”

Boy, how I agree with that!

I went from a failed induction turned cesarean with my first baby, to a home water birth with my 3rd baby, and in my personal experience (which means nothing scientific, but helps the story) pitocin contractions are hell on wheels compared to non-induced contractions. In my professional experience as a doula, I can also say the same. Even my clients WITH epidurals cannot often handle the pain caused by a pitocin-induced contraction. They are horrendous. Of course, I think what really contributes to the Pit-pain is everything else that surrounds the procedure. If she’s got Pit, she’s more than likely strapped down with CEFM, and we all know that strapping a laboring woman down creates a lot of anxiety and more physical pain than allowing her body to be upright and mobile. Of course, the brain is also not releasing those awesome beta-endorphins that accompany natural oxytocin production either. I’ve known few moms who can handle Pit contractions without the epidural, and they honestly blow my mind. Huge kudos to them.

I have to agree with this 100%! I have been induced with all three of my children….1st one out of ignorance and doctor’s schedule, and the 2nd and third because of failure to progress with concerns due to gestational diabetes…after being 4+ cm dilated and 70+% for 2-3 months with each….my body never progressed even with pitocin until after my water was broken. With the 1st 2 I was “strapped down” and it made me crazy…far more than the third where I was “allowed” to get up on my hands and knees (more like I didn’t care what they said and did it anyway…) where the baby instantly dropped and I went into HARD labor….pitocin levels were way too high for all 3 leading to back to back to back contractions the entire time I was in active labor…luckily each one only took 20-40 min to push out! I did not have an epiderural, it was not an option I was willing to consider, but man did the nurses try to convince me! Poor ladies got their heads chewed off several times in the midst of labor for that one…

I did it. I opted to have a natural birth without the epidural. However, as my labor did not progress, my baby became distressed, so they recommend pitocin. As soon as they started the IV, my contractions went from painful to extremely unbearable pain, I really thought I was going to die. I never accepted the epidural. Later, my OB mentioned how rare it was to go that route (pitocin – epi). Im really glad I did not have it as it allowed me to be free from the confines of a bed and labor all over the room, bath, stool, ect.

well, I just think that each birth for each woman is different and sometimes even a physiological birth can be intense and challenging: too fast, too slow, too “whatever”- and perception of pain is heavily influenced by the circumstances surrounding the birth. I don’t mean to minimise a woman’s experience of induction by my comments – just that the uterus contracts strongly and intensly for every labour (spontaneous and induced) , and perhaps the perception that the pain is worse in an induction is more to do with the associated factors as I listed in my original post. it’s based on many years of reflexive practice – observation and reflection on women’s birth stories/debriefing/sharing with me

That may well be the case Maxine, but pain is whatever the woman says it is. And we know that pain is so much more than a physical experience. So even if the lived pain experience is worse because of the associated factors you mentioned, and not purely physical/physiological ones, this is still the woman’s experience of pain, and is no more or less valid than the pain experience of normal contractions.

exactly – what she says it is is what it is.

Very interesting Maxine – I’ve has similar experiences with my hypno Mums. Expectations and emotional state change perception of pain and I’ve had lots of Mums go through induction without needing an epidural and they found it manageable. I’m a 3rd year student Midwife and I find that women are told to expect induction will be unbearable and will need an epidural by staff and by other Mothers. Mums in our care are in a highly suggestible state. Why not ‘suggest’ to mums that inductions can be quite manageable for some women and they do great without an epi?

suggesti

thanks Tracy, you seem to understand what I’m saying – I do hypno preparation with women too and perhaps thatis what guides and influences my attitude to a woman’s expectation/perception/experience of her birth

Good thinking! I agree!

Gotta say that most women (myself included) would beg to differ about induction and physiological contractions feeling the same. No way on earth! For whatever reason, be it the altered and fearful circumstances which dry up the endorphins, or the dosed, relentless application of strong hormones, most women who go down the prostins/syntocinon route end up needing an epidural. I do think that, as hospital midwives, we owe it to the mother to explain as gently and positively as possible, alllowing her to have time to absorb the (full) information. We should also allow her to say “no” – something which is often not an option when accompanied by horror stories about what might happen if we waited. The most common reason for induction is “post-dates” which is often based on faulty or lazy calculation of gestation in the first place.

Thank you so much for this post. It is a great fact-filled summary of the process of IOL in hospital, and one I’ll be able to recommend to women in general, and my follow thru’s, if they are considering induction. I’m a 2nd year BMid student and I’ve just finished a 4 week block of clinical placement. I saddened me that so few normal, uninterfered-with births occurred – didn’t surprise me, but saddened me nonetheless. I’ve had 2 kids to date – the first born at 43+1, the second born at 43 weeks. I did have monitoring with the first, but not the second. The cultural pressure was there to be induced, but I wasn’t interested in the alternative, so I waited. What else was I going to do? I’m so very glad I did. And so very grateful for my wonderful, trusting midwife who was willing to wait with me.

So many women are surprised when I say how long I’ve been pregnant for. The usual incredulous response? “They let you go that long/far over?!” My response? “Who is they? It’s my body, my decision, my baby and we were fine so I chose not to fix what wasn’t broken.” The usual reply? “Wow, you’re brave/patient!”. “No. I’m stubborn/trusting/it’s sheer bloodymindedness!”

(And for the record, I can tell you about 4 points in my first labour/birth or even before where I would have been ‘recommended’ for a C/S – an unnecesserean as it would have been.The fortitude and support I had which allowed me to birth my first normally has changed the course of my life forever, for the better. I don’t know the path not taken, but I suspect I’ve seen it a number of times in others, and I’m glad I chose not to walk that path. I am forever grateful to my midwife/midwives who took the path less travelled with me and facilitated an empowering birth which has made me feel I can do ANYTHING!)

“which has made me feel I can do ANYTHING!” Love it!

I love the ‘road less travelled’ comment too! Any ideas how to make it a superhighway?

One at a time Carolyn…at least that’s what I tell myself (over and over again, especially on placement!). My mantra this year has been ‘starfish’ (see link… http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=184161658288110 – I am unable to determine the original author of this story, nor it’s truth in fact, but the analogy remains valuable nonetheless).

It’s a bit like direct selling I guess – one person buys a product, shows it to their friends, their friends show it to their friends………… I hope, at least.

You awesome, experienced, wise, privately-practicing midwives who write easy-to-read and access, evidence based and referenced blog articles that we can post links to for other students, or on facebook – you are the ones allowing us inexperienced ones to share the reasons and logic behind taking the different road. You have seen what we haven’t, and sharing your knowledge allows us to make a difference in our own and others’ lives.

Thankyou.

hopfully me too!

Hi there, this is a very timely reminder for me. I live in Qld and am currently 30+4 weeks with number four. All of my children have come into this world via induction. With both our boys I ended up with an epidural and my daughter came so fast there was no time for much apart from gas. I am almost certain that my first induction should never have happened. My body was not ready but without realising it, my midwife (he was born in NZ) was very much into intervention. She had too many clients and I sincerely wish I had seen that at the time. Needless to say, his birth was the most traumatic (vacuum extraction) as he was coming out the wrong way up and an epidural that made my legs so dead they had to be in stirrups. All of this made for a hideous experience which I am working really hard to move through. This time I am determined to let my body and baby do what it needs to do. There will be no medical intervention (unless there is a ‘medical’ reason for the baby or myself). Our bodies are made to give birth and I owe it to myself to trust my body for my baby and I, and our wellbeing. I always thought birth plans were something for those who had big aspirations but I will be writing a very basic one for this time. I give thanks to my husband who is an amazing support person and more than prepared to support any decision made. Thank you for a great piece of information for all those considering induction. Even though I have had three, all three have been different. I am so pleased to have found your page and look forward to reading your blogs.

Thanks for sharing Sacha. Check out 10 month mamas on facebook for some support. I am a mum who has birthed at 43+1, and again at 43 weeks. I know the pressure to induce, and what it took for me to wait…and wait…and wait! It can be done, but it requires mental readiness, preparation, support from significant others, and an understanding of the alternative (which you are already very aware of!). Good luck this time around.

Thanks Anna. I will check out that page. I had a midwife visit today at the hospital where we wrote a very short birth plan. I told the lovely young midwife that I would like to avoid an induction this time as all three of my previous births were induced. She was very supportive of my wishes however did state that they would not let me go past 40 +10 days as research had shown the placenta starts to fail after this time and the baby doesn’t get the oxygen and nutrients it needs. I thought at the time hmmm … this sounds like standard jargon to me. I obviously isn’t too harmful if there are mummies who have delivered significantly later than 40 + 10. So, as it stands they are supportive to a point but I wonder as time draws closer, how they will approach my stance on induction. Will keep you posted :o)

Ask her to show you the research… There is NO research that supports the theory that a placenta shuts down at a specific point in pregnancy. This is only a theory and one that Sara Wickham does a great talk on ie. how stupid it is. The placenta doesn’t have a best before date. I have seen juicy healthy 43 week placentas and scrappy calcified 37 week placentas. Term is 37 to 42 weeks – even by text book standards 42 weeks is normal. This mis-information makes me fume (can you tell).

“they would not let me go past 40+10 days”… what are they going to do physically enforce an induction or c-section and get charged with assault and battery?

It is not their job to ‘let you’ do anything or tell you do do anything. They provide information, you make a choice, they support your choice – easy.

Looking back, it was a miracle that I wasn’t pushed into a C-section at the last minute like so many induced births are. I was very overweight. The doctor’s visit that I initially went in for ended in the hospital a week before my due date because the “baby wasn’t moving enough.” I later found out that the reason for that was because I was in the initial stages of labor. I was hooked up to a blood pressure monitor all night, which painfully took my blood pressure every 30 minutes- effectively removing my ability to sleep the night before giving birth. Exhausted, the next morning they started me on Pitocen which began to speed up the little bit of labor I had left, since my body had almost completely stopped contracting on its own. The doctor then broke my water as the nurse kept upping the amount of Pitocen going into my system. The shock and pain of all of these things happening at once, though I didn’t want one, had me asking for an epidural. This was the first time I was able to sleep in 36 hours. This rest allowed my body the time and resources it needed to hurriedly get ready enough, though everything was still so rushed. Nurses came in every two hours to check my cervix. I prayed the whole time that my body would just cooperate and I wouldn’t have to get a C-section.

I’ll finish this part of the story just by saying that I did give birth to a healthy little girl. I was so exhausted and disconnected from what had happened that it didn’t even seem real. I couldn’t bond with my baby. I couldn’t nurse. This only spiraled into a postpartum depression that got worse. I fought depression and pumped for four months trying to learn how to nurse before we finally figured it out. There is nothing I have faced worse than my baby screaming because she was hungry, and I was there ready to feed her, but we couldn’t figure out how. In my mind, at least, that lack of bonding and problems with nursing all seemed to come as a steamroller effect beginning with induction.

Great post as always Rachel. You always seem to come up with exactly the right information at the right time for women. Given the latest figures on the rate of induction in this country it is so good to have this resource to help women and their partners know what is involved with what seems like such a simple decision. I’ll be sending this information far and wide!

Hi Denise! I guess the hardest part is making the decision to induce or not and weighing the risks…something that isn’t easy when you’re carrying another little you around in your belly. Thanks for this detailed post and I have a copy of your dictionary right beside me 🙂

Adina, your story is heartwrenching. Sadly, you are not alone with your feelings and your reactions after such an experience and you are right, induction is the beginning of that roller coaster for many women (too many and increasing as induction rates skyrocket). There are many aspects to the way that the induction process influences the bonding and breastfeeding complex – hormonal level changes, intracellular and intercellular fluid level changes and other complex changes in all physiological and neurological interactions from the minuscule to the huge ‘system communications’ for both mother and babe. I do hope you have been able to heal from that time of disconnect and that your relationship with your daughter is improving in leaps and bounds.

“Basically, it can be pretty nasty stuff which is why your baby will be monitored closely using a CTG.” You’ve got that right; pitocin isn’t even approved for the FDS for labour induction or augmentation!

http://www.birthroutes.com/home/2010/5/30/pitocin-not-approved-by-the-fda-for-elective-or-non-medical.html

My membranes released spontaneously at 39+5 without contractions. As I had tested GBS+, this put me in the high risk “you-need-to-be-induced-RIGHT-NOW” category. I resisted being induced (i.e. with syntocinon) for several hours until they finally bullied me into taking prostaglandins, which was presented to me as a “reasonable compromise” option. Naturally the waterbirth I had planned was off the cards now, except that 24 hours after my SROM and about 6 hours into established labour the obstetric nurse on duty “let” me get in the bath. (She didn’t believe my birth process was established yet.) I experienced as close to a “normal” birth process as you can get with an induction (i.e. no AROM, no synto until third stage, but plenty of interventions on the side like VEs, CTGs, and other standard hospital fare), and it was the worst experience of my life. One of the things that upsets me so much 4 years later is the way they made it sound like induction was so urgent, and that I was taking such a dangerous risk by refusing it, and yet once they had determined that I was one of those pesky patients who wanted a “natural” birth and would resist all suggestions for intervention, they left me more-or-less alone until I was pushing a day later. What happened to the urgency? It wasn’t urgent at all, they just wanted to feel like they had control. If only, if ONLY I had not agreed to the gel! (Or better yet, if only I’d stayed home in the first place…)

OK folks – I’ve added a bit to the posts about pain because I obviously didn’t make it very clear first time around.

Thanks everyone for your input – especially the birth stories. I know that women find other women’s experiences extremely useful 🙂

I guess this post raises many issues in additon to the original (improving awareness of the process of induction). One thing that often strikes me is the lack of questioning about a particular investigation & what might happen if the result is other than normal or what we want…when we check the nucal fold on USS, measure a woman’s blood pressure, do a GCT or GBS swab, USS to check the placement of the placenta (to name just a few of the multiitude of antenatal investigations) it is to assess for the presence of pathology that might need further monitoring or treatment. I don’t think enough explaination about these tests and the subsequent intervention that might be offered/suggested/insisted upon takes place prior to the investigation.

At the end of pregnancy, it is not uncommon to have the fluid around the baby measured (AFI) – if the level is adequate, it gives reassurance that an induction is not indicated and waiting a couple more days for spontaneous onset is an appropriate choice; if the level is low it means the placenta is probably declining in function and induction is appropriate. Despite this, oftentimes the AFI is done and the results disregarded. I think to be a good midwife (obstetrician) we must always start by practicing “expert inactivity” but also acknowledge when the process has deviated from normal. This means acknowledging the value of (judiciously applied) intervention and medical technology and help support and guide the women for whom we care in the grieving that invitably takes place when the birth is no longer the one they had planned & fantasised about

I was so young (well 25) and clueless when I had my first. He was due on the 11th December and they told me that I would have to be induced on the 15th. No one ever said why, but I think now that it was to do with Christmas approaching and staffing levels. Ended as an emcs as my son didn’t like either the syntocinon or the epidural.

A client of mine was taken into hospital on a Sunday evening to be induced because she had OC. She was told that her baby would die without induction. They gave her gel on Monday morning, again in the early evening. Forgot about her all day Tuesday because they were too busy. Wednesday she fought them to go home for a few hours, which they reluctantly agreed to after telling her her baby was a great risk. She reminded them about Tuesday. Wednesday evening more gel. Thursday morning more gel, Thursday evening syntocinon. The baby was finally born on Friday morning. She said to me “They scared me into it by telling me that my baby would die and spent five days ignoring me, except for when they put the gel in.”

Thank you for such a great article about induction. It is now in my resource pack to give to clients that want to know what induction is all about.

Mars xx

I had PROM at 36 weeks, and after 48 hours was told to go into hospital “to be checked”. When I got there a junior doctor said that she was going to do a VE “to check whether my waters really had broken”, but I declined, saying that if they hadn’t, all well and good (they – er – had), and if they had, well we would be introducing bacteria which was a really bad idea. She said that it didn’t matter as they would be inducing me later that day! I’d gone in to be “checked”!.

I said that I wasn’t prepared to be induced, and she told me that it was dangerous. I asked why, and she didn’t really know, but just said that induction was just what they did.

I was then referred to a more senior doctor because she really didn’t know what to say to me. Cue a lot of pressure to go for the induction, because the baby could be at risk of infection.

I then started ask – what was the risk of infection? What was the potential problems that might happen if infection set in, and what were the chances of infection? She argued with me that I was putting my baby at risk (blah blah, we all know this stuff) and then passed me to the senior obstetrician in the area.

When he came to see me, he was brilliant. He actually explained the risk – that infection could be very serious or even life threatening to my baby – but that the risk of an infection setting in was small, and he acknowledged that the risk of induction and the risk of complications from thiings like CS were also significant, and much more likely to happen.

I then asked what turned out to be the critical question, which was when a mum’s waters broke really early in pregnancy, they couldn’t induce so what did they do? The answer was to keep a careful eye on the baby with monitoring, and to carefully watch mum for infection by regular (2 hourly) temperature checking and blood tests. If anything seemed to be going wrong then we were to keep an open mind about options. It was also recommended that I had IV antibiotics in labour to sweep up any infection which may be starting, and while I wasn’t happy about this, I felt that it made sense.

In the end I went into SL 5 days after PROM at just 37 weeks. I had a straightforward labour, TENS machine for the first half then pool for the second, and my little one was born peacefully and serenely underwater with no damage to me at all. He was a bit squashed and stiff from being without fluids for so long, but some cranial osteopathy helped that over the next few weeks.

He’s just turned 1, and tragically a few weeks ago there was a big news story locally about a baby who had died post delivery following a mum delivering several says after PROM. From what I can gather from the news (where obviously you can’t actually know what happened), the mother was somewhat left to her own devices and not properly monitored. Even so, we were aware that we were taking a risk – and some might say that you should never risk your baby’s life – as they drive their little one home from the hospital. Nothing is risk-free and for us, the risk of induction was a much higher risk than the risk of infection, which is a hard decision to make when the risk of infection can be so serious.

My husband and I essentially forced the hospital into giving us what we felt was a pretty basic standard of care, and by doing so we created a lot more work for them. Sadly, I feel that it is only because of this that induction following PROM is the way people are strongly impelled to go, because to ensure that the very best is done for the baby without induction, careful monitoring seems to be essential, as well as trust in the parents that they will actually tell the doctors if signs such as a raised temperature are starting. Let’s face it, doctors don’t tend to trust women 🙁

I wanted to write my story to show that induction isn’t always forced on parents, and asking “why” means that you CAN, sometimes, actually be involved in your own care. It was not a walk in the park. It was one of the most stressful weeks of our life. But it worked for us.

this is a great post – thanks for sharing – and really highlights the importance of asking “what if” when exploring all options and weighing up risk (and what constiutes a risk for YOU, not necessarily the staff). Well done for having the sense to ask ask “what happens when water break really early in pregnancy” because it is something I have thought of too – that some women sit around for weeks with ROM waiting for the baby to grow but others are whisked in within hours of induction “because it’s a risk to wait”. It takes real courage and fortitude to stay the course of your convictions, and also it sometimes takes luck to encounter thoughtful staff that consider your input in the decision making process.

I think if there is honesty from the Doctor in his answer ( a bit of heart), then the outcome is wonderful…

When I asked ‘why’, I got a lie…and believed it…..So it depends again, on who is answering and if you are well informed yourself. If you are not, it is easy to fall into the trap of ‘Doctors know best’ as long as my baby is safe…..Thanks for sharing your story.x

I don’t know where to start with my “story” it could be quite long. This is a fantastic blog and I thank you for outlining the information in an easy to read/understand way. I would love some input from you about my induction. I started latent labour naturally at 40 6. I didn’t know at the time but my dd was back to back. I continued to contract until 40 12, contraction were never further apart than 30 mins but very often were every 2.5 mins sometimes for 6 hours. I managed the pain (I have HMS and SPD) for the six days with bath after bath and a tens and paracetamol. On 40 12 I had SROM in the bath and was advised I needed to be checked over. At the hospital they discovered meconium in my waters so sent me to the labour ward (from a birth centre). They discovered that not both parts of my waters had broken so AROM on the other part, I was two cm dilated. They attached a syntocinon drip, I never once contracts regularly and five hours later the contractions were out of control (i had an epidural at this point) and going 6 in 10 mins then 1 in 10 if they turn the drip down. The circus of internals, drs checking the trace ect ended 16 hrs after it stared by EMCS. I had dilated to 8 cm in that time but my babies heart beat had dropped and she was in distress:(I had so wanted a natural birth. I know now that one intervention usually leads to another and so on but I can’t decide at what point my first intervention happened? How could I have stopped it all spiralling out of my control? I did visit the hospital twice in the six days before the induction and was turned away because I wasn’t in established labour so I was examined on each occaition. They also used the CTG at one of the visits because they didn’t believe I was contracting as frequently I said and not progressing well for the duration I’d been in latent labour. So was my first um necessary intervention the first visit to hospital, the first internal, the paracetamol I took at home? The subsequent hospital visits, the other internals? The trace? Where does it start? I think as I’m writing this that it might be the first internal/visit. If I didn’t know at that point I was only 1cm and cervix not favourable then mentally I might have progressed naturally? Can anyone give me any information or thoughts on my experience? Sorry it’s so long.

Shelley. You did nothing wrong. You didn’t fail. You did exactly what you needed to do in a trying situation. Others with more experience may be able to shed some light on your birth, but you need to know you did what you needed to do at the time. It’s hard, and it can’t be changed, and hindsight might be useful, but it doesn’t change the outcome for this birth. I wish you peace and healing from, and acceptance of, a difficult situation, and that you can take the pressure off yourself.

Thank you Anna, I know a lot more now and I plan to home birth my next. Hindsight is useful and I will learn from it and move forward. I guess I just want to know if it was all inevitable form the start or if I made it happen, but i’ll never really know.

Thanks Anna – exactly my thoughts.

I am sorry that your birth experience was like this. It really is impossible to say what might have happened differently – hindsight is a wonderful thing. You did the best you could with the knowledge you had at the time.

In the US, I was told that I *could* leave the hospital after a failed induction, but only if my water had not been broken and I did not have an epidural. Also, I would not be given another scheduled date for induction – so if my pregnancy continued past the point where I was comfortable, I would not be given another date/appointment. The key is that the water not be broken, and my understanding is that it is in most induced labors (only after labor is induced by some combination of prostaglandins/synthetic oxytocin), because the chemicals are not usually enough to get labor going on its own.

Some hospitals will abandon an induction but that just reinforces the fact that induction was not necessary ie. that the pregnancy continuing does not put the mother or baby at risk. When I first started midwifery we used to administer prostaglandin then after a few hours send the mother home overnight to come back for her next dose in the morning. However, there have been a few deaths associated with mothers going home after prostaglandins. So, the hospital changed its policy and everyone had to stay in until the baby was born.

My story’s similar to Shelley’s — the day after my due date I had partial PROM (a very tiny amount in retrospect), followed by latent labour, pressure to be induced due to infection risk (which I resisted), finally agreed 48 hours later for the rest of the waters (which had “thick meconium”) to be broken, then after nothing else happened a few hours later, agreed to oxytocin drip. Cue several hours of the most pain I’ve ever experienced in my life before I could get an epidural, then told not to push at 10cm even though the urge was strong, then directed pushing right after epidural top-up, baby never really moved, and the whole thing ended in EMCS after I refused to let them at me with the ventouse.

By that point I needed a known outcome and EMCS seemed like the best choice (how bad does it have to be that EMCS starts to look attractive!) Thankfully the baby was never in distress but I certainly was. Have recovered from the EMCS but as the whole experience was so far from my desired homebirth, I’ve been left wondering if I could have done anything different, or was my baby destined to be born by CS?

Not gone into hospital after waters had broken? (I did because I had a low-lying but safe placenta and was told I had to go in if I had any bleeding or waters breaking). Waited for rest of waters to break naturally? (They were afraid of cord prolapse, so that’s how it was sold to me to have ARM). Not agreed to be induced? (By then I was told I had no other option and I was out of energy fighting against it).

What are the choices really when you’re faced with these situations? I’m planning to get a copy of my notes and have a birth debrief but I honestly would like to know what other options I could have had.

You did the best you could with the mis-information you were given. I suggest you take someone with you to your debrief to write things down – as often you forget what you are told. I also suggest you talk about this with someone outside the hospital ie. an impartial person. I makes me angry that women are left with all these questions after their births 🙁

Just curious then — if there is a small PROM (forewaters I believe it’s called?) and no labour forthcoming, no other complications or health risks, what do you advise women to do? Monitoring for infection… for how long is it safe? When does induction become a useful thing to do — or should it be avoided at all costs (which is kind of how your original post comes across?)

I don’t give advice only information 😉

Read this post http://midwifethinking.com/2010/09/10/pre-labour-rupture-of-membranes-impatience-and-risk/ it might provide you with more information about this situation. Induction can be a useful thing and can save lives. Some women will choose to be induced even without a medical indication, and as long as they are fully informed – it is their choice – no judgement from me. Safety and risk is an very personal and individual concept.

By the way – it is called ‘augmentation’ when your waters have already broken. Not sure why as it is basically the same thing.

While I quite agree with all the principles of your article (even though four of my six labours were induced), I have to take issue with the term “physiological birth” much the same way I take issue with the term “natural birth”.

Physiological is defined as, of or pertaining to biological functions, or consistent with the normal functioning of an organism.

Whilst my labours may have been induced or augmented, the process of the baby getting out was most certainly a normal, joyful and extremely biological process in which I was fully engaged and which resulted in babies being born vaginally, happily and healthily. However the labour was begun, the births were all normal and uneventful. It’s ridiculous to define that as somehow non-physiological. My personal anecdata aside, it’s alienating to women who have undergone medicalised births to somehow imply that their births are “less than” by appropriating language that actually, really does still apply to them.

I am sorry if the word ‘physiological’ is taken as a judgement. That is not how it was meant – there is no ‘less than’ or ‘better than’. But, I will continue to use the word because I like to call a spade a spade and be honest with women. Although an induced labour can be uneventful, normal, joyful, even empowering – it is not physiological. Natural oxytocin is released differently and is able to work on the brain (vital during a physiological birth). Artificial oxytocin only works on the uterus as it cannot get through the blood brain barrier. Induction is not ‘consistent with the normal functioning of an organism’. If you want to know more about the physiology of labour hormones check out the work of Sarah Buckley (you can download her ebook here) or Michel Odent (you can find his research depository here). Moberg has also written a book about oxytocin and it’s behavioural effects in mammals (and humans) –

the oxytocin factor.

I think it is unfair to pretend to women that the physiology is the same. Some women want to know why they ‘felt’ different during and after an induced birth vs a physiological birth. In some cases they also deserve answers about why breastfeeding may have been difficult, or they found it difficult to bond with their baby (ie. they did not get the behaviour effects of natural oxytocin). There is lots of research going on at the moment looking at the role of oxytocin in bonding, breastfeeding, postnatal depression, autism etc. I hope I am not alienating women by being honest but I can’t pretend the physiology of an induced labour is the same as a physiological one and deny the science.

Are, here is the bit I was searching for, that natural oxytocin works on the brain whilst syntocinon can’t cross blood/brain barrier. This made so much sense to me when I read about oxytocin, as to why IOL’s are so much more painful. I wish Obstetricians would read about oxytocin rather than deriding midwives’ knowledge of hormonal actions on labour & birth.

PS I am a hospital midwife who is in a funk and found your blog whilst seeking articles for my master’s assignment. keep up the good work!

Oops, meant ‘Ah’ not ‘are’ LOL

Thanks for yet another great article and on a subject that so many women face – isn’t it scary how many women are induced simply because they reach a certain date in their pregnancy (never mind whether or not mum and baby are healthy and happy)? I often worry about the idea of women having an ‘informed choice’ about induction as there is such limited information out there concerning all the steps involved (the excellent AIMS booklet on induction excepted). I will certainly be recommending people to read your article.

I was induced all 3 times, for medical reasons. I did it without an epidural. The first time, I had very high BP/eclampsia, my second was stillborn, and the third was a combo of gestational diabetes/eclampsia/BP again. I did have a morphine drip with the second one, but that was mostly for the mental issues of dealing with having a stillbirth. I actually had very easy labors until the last 25 minutes or so. I am assuming I was lucky, and that is not how induced labors usually go? I just want women to realize that there ARE legit reasons for being induced, and that does not make us bad parents for choosing it when needed. If I had not been induced that first time, I would be dead, and so would my child. What purpose would that have served? That being said, I think that being induced because you are “tired’ of being pregnant is ridiculous, but it does happen.

Amy – induction of labour saves lives and is a necessary intervention for some women like yourself. I think you were lucky – but interestingly I have noticed that when there is a medical indication induction often works better. I’m not sure if it is because your body ‘knows’ it needs to get the baby out. Anecdotally midwives talk about knowing it was ‘real pre-eclampsia’ if the induction was quick.

I know I was lucky.And I am thankful. I have heard how painful an induction can be, and I very much wanted to avoid an epidural/pain killers. And i did! 🙂

So sorry that you lost a baby, not very lucky at all. High BP does tend to make labours progress more quickly and you were very wise to agree to a induction in light of your obstetric history. There certainly are valid reasons for having an induction.

AS I have said and learned from experts years and years and years ago. Babies of mothers with pre-eclampsia have a cervix ready to come into labour – the baby has an ejection reflex that appears to get things moving as well. Pre-eclampsia itself is silent with signs only of a small baby for the length of gestation – stated many times by the old consultants who did not make much money out of their philanthropic donation of time. Often the first sign after “small baby for dates’ may be early labour or even term labour. When a member of staff came in to emergency with symptoms of headache indigestion and double vision, – as well as contractions – I wheeled her to the birth suite and within seconds she was convulsing that is having an eclamptic fit (old language kidney fit – because of damage to the kidneys from this condition).. Her bush doctot a GP, had not taken the indigestion seriously – she had been given a bottle of Mylanta and Panadol for the headache. All the cardinal signs were there. 1. Raised Blood Pressure 2. genearlised oedema and 3. proteinuria. I do not want to ever repeat that experience – she survived and the baby became a ballerina. That is Only 1 story.. The question is would all of that happen if she had seen a midwife and a home birth? I ask that about every hospital birth gone wrong.

Just realised I am supposed to ‘REPLY” to the person writing” – must not sit here too long lots of bills to pay online and a talk on bush tucker to prepare.

IThank you for starting this conversation this is one of my stress producing subjects apart from Unnecessarians being the other..

I haven’t read all of the above but at the outset I invented the name Obstetric Cascade just after I had given a lecture to Mercy Hospital Students on the cascade of the pregnant and normal process of clotting formation and effects of haemorrhage in the early 1980’s . Many of my colleagues and the women and some men were already on the path to highlighting the harms of 15% induction rates. Submissions to the Victorian Goverment’s Interim Birth Inquiry came on about that time. In 1989 Maternity Coalition Victoria was formed some of whom were on the board of that Inquiry.

My advice for normal physiological induction is to wait for a full moon accompanied by an electrical storm (may work on its own) and/or use nature’s method of sexual intercourse taking a long time over foreplay. Apart from the mechanical action the semen contains a good dose of prostaglandins (mega doses of synthetic hormones are in the gel and the oxytocic infusions) hopefully orgasm for the woman (often stimulates uterine contractions – false labour for some during the preceding last 3 months). Sexual Intercourse for pregnant women is not harmful, (despite one of my mothers-in-law telling my husband that it was?! ) in fact it should be good for you before during and after pregnancy. The semen contains minerals and the action is essential for keeping all plumbing in good working order. It helps each other to gently heal wounds and is an expression of mutual love – I often wonder when I see some women screw up their face at the suggestion – but I have planted the thought and suggested it is OK>

I wonder about inductions when the baby is compromised – I was taught by the gentle men of obstetrics that pre-eclampsia was not a reason to induce as pre-ecamplsia itself was a precursor or instigator of early labor. That is the baby decided to get out early often presenting with premature labour and often unrecognised by unskilled or inexperienced health carers.

It was more important to recognise pre-eclampsia by monitoring pregnancy. Family history and previous history (except if the partner has changed) sometimes is an predictor. Although once recognised rarely re occurs because of awareness and better care.

The first and earliest sign is small baby for gestation by manual assessment plus the cardinal signs of rise in blood pressure diastolic by 10 mm hg and Sytsolic by 20 mmhg or more.

Generalised oedema meaning the lower back and shins as well as tight rings. Protein in the urine on testing. Late symptoms of frontal headache, indigestion and double vision is usually a late symptom and this becomes an emergency treated medically first with oxygen to the mother and durgs to avoid convulsions .All other conditions ought to have been excluded such as chronic kidney disease or infection.

The woman once recognised should be rested with vigilant monitoring before any intervention and have the baby in optimum condition before birth. But of course now no one has time to rest and wait there may have been improved changes in management with better outcomes. I question the inductions with long strong hard contractions from Syn tocinon infusions or frequent small contractions over a long period due to the gel with its dangerous Misoprostel and Cytotec, which results in pain due to nature not supplying oxygen to the uterine muscle. All of this in the mother’s system with an already compromised baby. That is a baby which is being already deprived of continuous nourishment and oxygen in the uterus. Others have said this on Face book and I have watched in horror as women unquestionably submit to this SOMETIMES necessary but often only done in the interests of speed and saving time.

One woman stated “Just how fast do I have to go?”

I was monitored very closely. I was on bed rest for a month(starting at 34 weeks) sue to protein, swelling, and high blood pressure. Strict bedrest. Only getting up to use the restroom. I was doing NST’s twice a week. By week 38 , my BP was way to high, and nothing was working. That is why I was induced. I was exaclty 38 weeks when Megan was born.

Thank you so much for writing such a great article! In Poland induction rate is almost 60 % :(( Can I translate it and share it online (Facebook and my forum) in Polish giving a link to your blog? I haven’t came across such a great and simply written text about induction yet in my language. I’m a hypnobirthing GentleBirth teacher in Poland.Thank you for all you hard work on this blog. I love it!

Of course you can. I’m flattered that you want to 🙂

both our boys (now teens) were induced and I have no problem with that. why should I? They were very large babies – the first 9 pounds six ounces and the second 9 pounds 13. I delivered both vagnially, one with pain meds one without.

I do think had these pregnancies continued so too would have the likelihood of a c-section.

I breastfed them both.

Congratulations on breastfeeding as sometimes these inductions lead to operative delivery. Due to a now 9 — 12 hour time limit on waiting for inductions to work Caesarian birth rate have soared in private hospitals up to 50% in Victoria.. Caesarian births are linked strongly to low breastfeeding rates with many not going past 3 months. This leads to cows milk (meant for calves) formulae Allergens from formulae are well documented as is the introduction of straight cows milk under 12 months. The early introduction of wheat based foods such as “Farex” ( before 6 months usually at 8 weeks) for most of the last century has led to the current explosion in “irritable bowel syndrome” translating to Gluten intolerance etc. The baby’s organs have not matured enough to produce Insulin at 3 months (AKre)

There is evidence produced by Beischer N, and Ratten, G in the 1980/s that babies generally do not gain weight at term or near term and they mention a reduction in liquor – which in my educated mind suggests the baby is getting ready to use its own fetal ejection reflex (See Odent M.) – synthetic based (prostaglandin./ oxytocic produced from horses urine at my last investigation) . Induction of course overrides many of these reflexes. . The findings of Beischer and Ratten revealed that they were actually recommending that babies do not need to be induced for “failure to gain weight at term”. In those days we though these guys were interventionists – but in contrast the current situation is diabolical. It is important to realise that

“one butterfly does not make a summer”.

Now I know the reasons for induction must have been to prevent further weight gain of your babies. I have heard of that as a reason. There are several given. Two of the most persuasive are “Your baby might die” or more subtle “If you want a healthy baby” . These are not reasons. One reason give to a client was because of a “rash” which had been complained about by the mother during pregnancy and which was ignored, but was made a reason when persuading the woman to have a synthetically induced labour?!.

Studies demonstrated that despite starvation diets women went on to produce large size babies in concentration camps in the early part of the Second World War. Other studies show that fat is laid down during pregnancy mainly on thighs and upper arms. Breastfeeding for 12 months and ideally 2 – 3 years will take up that fat – as most of us know getting rid of fat from upper arms and thighs is very difficult otherwise.

Dieting in pregnancy is therefore counter productive if you wish to maintain a milk supply. There are ample studies which state that that weight size had more to do with pre-pregnancy health and diet. The fact that you produced a big baby in the previous pregnancy should have alerted carers to the fact that your pelvis and musculature was able to birth a large baby. My neighbour’s 4th, 5th, and 6th children were over 12 lb. No stitches – all grew to 6 feet and over. Father and mother both tall and healthy as are the children and their children.

Others would be inclined to label large babies as pre-diabetic and your babies mistakenly labelled and treated as such – separating your babies from you to the special care nursery resulting in worried and stressed parents. Go view the babies of artists of the previous centuries. Artists such as Rubens painted in reality the newborn babies were huge, babies were breastfed and cherubic.

This is such a fantastic blog! A great article with many important explanations. One point I find needs emphasising to women booked for induction, is the fact that induction is generally a looong process & that it may well take 24hrs to even commence labour. I often see women arrive for induction with a whole entourage of family & friends excitedly anticipating the imminant arrival of baby. When we gently try to usher the party out so Mum can try to get some sleep before her body starts responding in earnest, people are often taken aback that they won’t be meeting bubs that night. Who is explaining (or rather, not explaining) the process to women before they agree?? Sadly, it’s Midwives as well as Obstetricians & it drives me batty!! Of-course all the portrayal in the media of rushing to the hospital at the first sign of anything remotely representative of labour before the baby falls out or both mother & baby die doesn’t help! In a perfect world health professionals would share their knowledge, provide complete & unbiased information & support the choices of birthing mothers ~ and women would take more responsibility for their health by asking questions & weighing options to come to decisions that are right for them instead of thinking they’d better just do as they’re told.

Good article. Another thought, women often ask for inductions as they are ‘sick of being pregnant’, and they don’t want to hear the truth of risks, the ‘cascade of intervention’ and increased chance of a caesarean. Women need to be more aware, and actually take on some responsibility of self education, and ask questions, before asking for an induction. We spend a lot of time informing women of why it is not feasible to induce their labour at 36-41 weeks when they are well healthy women. I swear that I spend more time researching what car to buy or paint colours to pick than some women spend learning about pregnancy, birth and parenthood.

You are right – some women don’t want to know and want ‘experts’ to make decisions. However, practitioners have a legal obligation to give them the information in order to gain consent – whether they want to hear it or not. Unfortunately many women don’t do the research until after a bad experience.

excellent info. but don’t forget, the oxytocin usually causes the contractions to be very intense and very close together. this pain is almost always the precursor to an epidural. trying to weather through this type of pain and contractions (often) less than a minute apart.. Very difficult. Sometimes leads to maternal exhaustion, which may result in emergency C-section.

WHEN it comes to medicine like this, the blog holds true, once your induced.. your labor is out of your hands. UNLESS MEDICALLY NECESSARY, DO NOT DO THIS. And please remember some OB’s perfer scheduled inductions vs. natural labor. They can control when you give birth vs.being called in the middle of the night to deliver. Or maybe theres more income potiential for an MD when induction is taking place? Of that, im not sure, BUT THE MAIN POINT IS “ITS YOUR BODY, and YOU need to take charge. DO YOUR RESearch! from a mommy of 4.

I was more than 2wks “overdue” with my first and went in for an induction. I was almost 2cm dilated so I went straight to the pitocin at 9am. I was not allowed out of bed unless to pee. Around noon I was 4cm and my water was broken. I was fine up until then. Contractions became unbearable at that point. by 2pm I got an epidural and I was still 4cm. At 10pm I was still 4cm and she was deceling to 90bpm during contractions. The OB said I needed an emergency cesarean because she wasnt tolerating the pitocin and it was at the highest she could put it. (pit to distress anyone?!) I said “No, if its the pitocin causing her issues turn the pitocin off” She said fine and told me that I had an hour to dialate or she would cut me. Not such an emergency was it? By 11pm I was fully dialated, on my own, no pitocin. 90min of pushing and she was born vaginally.

I am pretty sure had I waited another day or two my body would have gone on its own. My second child was a spontaneous natural homebirth at almost 43wks. My babies just like to cook. 48hours of labor(slightly acynclitic and nuchal hand) The contractions for his labor were totally different than my daughters and I would take his long labor over her induction labor any day of the week.

Just had a natural 2nd birth on Friday morning. Had practiced hypnobirthing this time so I know what you mean by the power of suggestion. It was all manageable and I found it exactly how I imagined it could be during my relaxation and visualisations. 1st birth 6 years ago I was made attend the hospital after 48hours for antibiotics as my waters had broken. I was told I was either 4or6 cm dilated. As I was told the drip would take hours and I had to be monitored on the bed the whole time I panicked as I didn’t really know how this would affect the labour progressing. What I did know is that as I had been on crutches for 3weeks with severe hip problem, lying on the bed in one position would be agony before I even considered contractions. I asked for an epidural which was granted. The whole thing then went on for another 15 hours in the same position in the bed – not good for my back! The consultant came in to do an assisted delivery after I refused the offer of a C-section. Once my hips where in the stirrups my hips were much more comfortable and baby 1 was delivered in about 5 minutes after the 4 day wait (every one was relieved). I know the staff just followed their guidelines but it took 3.5 years for my back pain to go away and another 1.5 for me and my husband to consider trying again. So regardless if the pain was ‘real’ or ‘imagined’ it has long term psycological effects on women which there is no ‘real’ way of addressing. I feel fortunate I found my hypnobirthing instructor who helped release my fears so I could move on. I know others who won’t have more children due to their negative birth experience.

“Although an induced labour can be uneventful, normal, joyful, even empowering – it is not physiological. Natural oxytocin is released differently and is able to work on the brain (vital during a physiological birth). ”

I’m also questioning the use of the word “physiological” labor not applying to an induction. My labor was “induced” via step 1 only- insertion of 1/4 tab of prostaglandin on a “ripened” cervix only…I was never given any pitocin. So it would seem that all my contractions actually were producd by natural oxytocin- right? This seems to be more of a “jump start” to a physiological birth. I also continued to be treated as low risk and was attended by my midwife.